The supply chain and global consumption of orange juice

In this chapter you will read about:

- The structure of the orange juice industry.

- The evolving relationship between orange growers and fruit processors.

- How marketing processors and bulk processors operate.

- The activities of blending houses, juice packers and soft drink producers.

- The fluctuations in the worldwide pricing of bulk juice products.

- How FCOJ is traded as a commodity product and the significance of the futures market to bulk trading.

- Import duties with examples in certain trading blocs and countries.

- The amount of orange juice products consumed in major markets.

Summary

Orange juice products usually change hands many times along the supply chain. It is thus important for all involved in the intermediate steps to be familiar with the total sequence of juice production.

In Florida, orange growers are becoming diversified agribusiness companies. In Brazil, the large orange processors still get part of their fruit from their own groves.

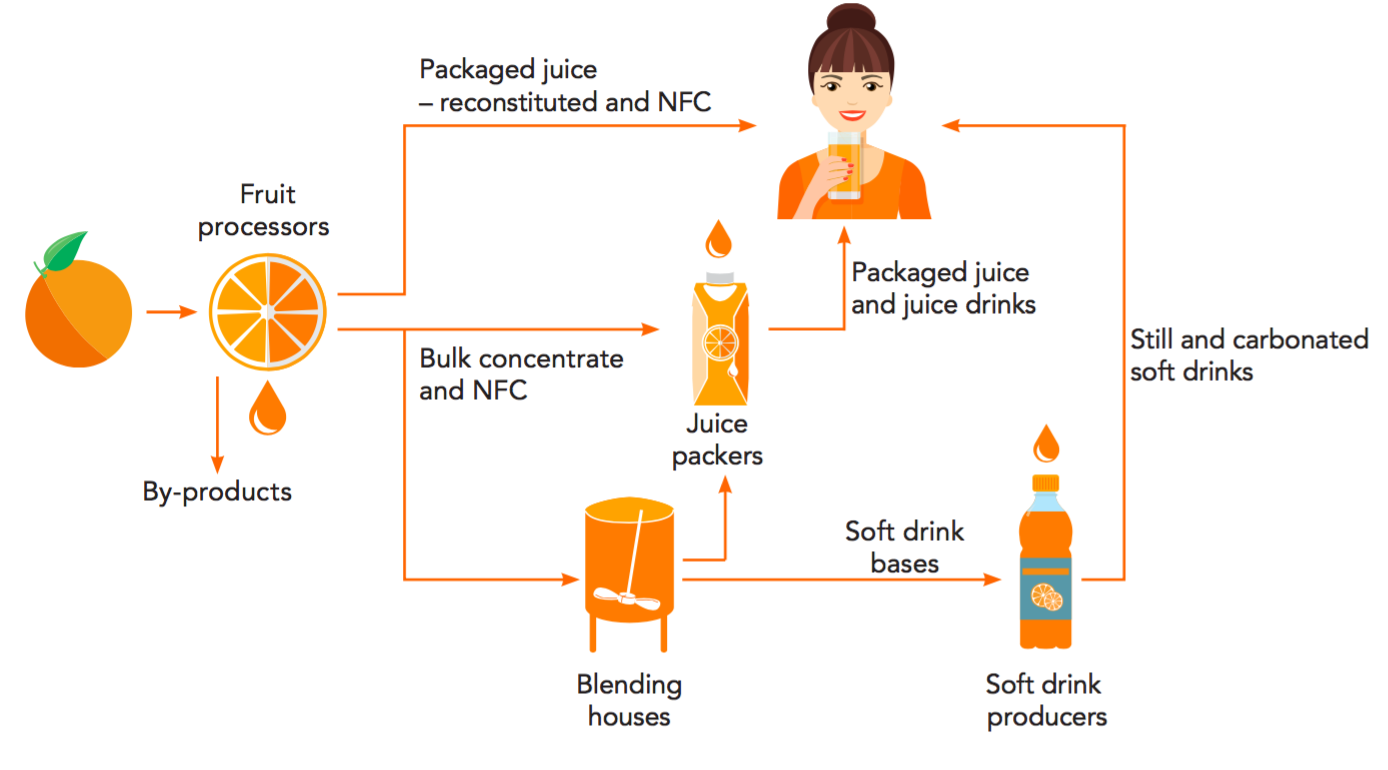

So-called marketing processors produce and sell their own juice brands. Bulk processors mainly sell their products in bulk form. Blending houses provide concentrate and bases of consistent quality according to defined customer specifications. Juice packers treat bulk product as required and then pack it in consumer packages. Soft drink producers may use orange concentrate and prepared bases from blending houses as raw materials.

Pricing and trading

Special terminals for handling frozen concentrate in bulk are located in major ports. The world market price of FCOJ fluctuates according to its supply and demand. Free carrier Rotterdam warehouse is a common standard for FCOJ (66 °Brix) traded prices, which include freight charges to the port of Rotterdam in the Netherlands.

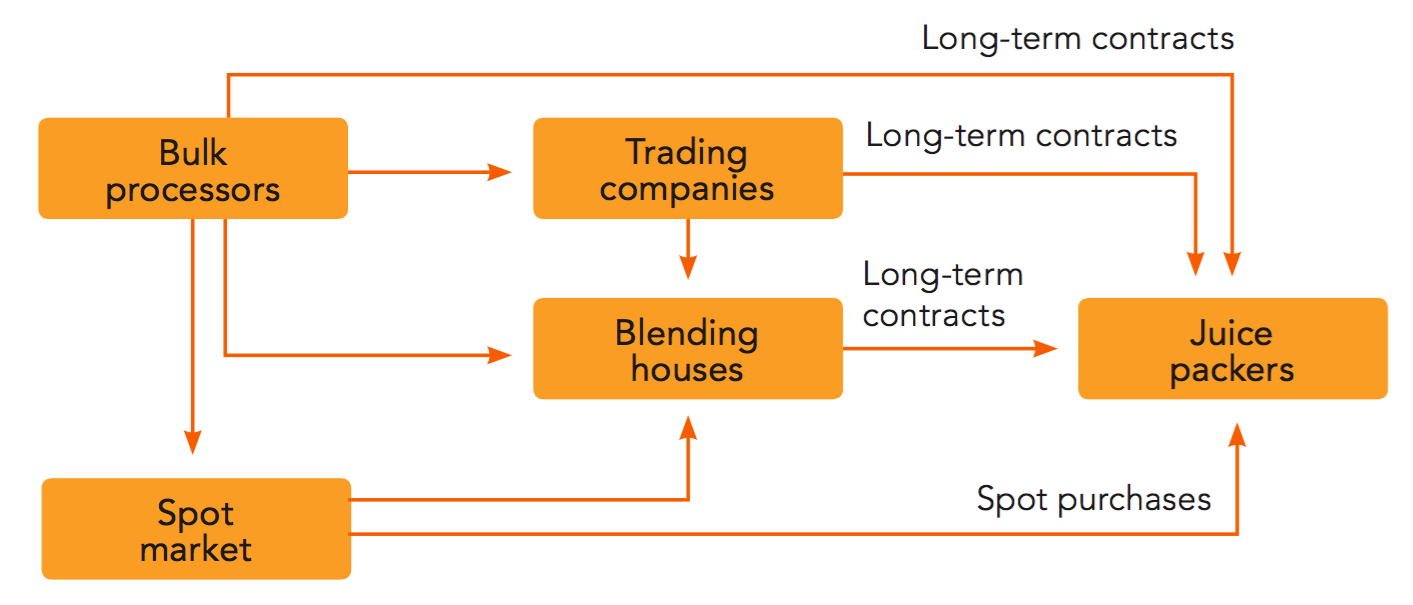

The futures market enables the citrus industry to manage commercial risks. It also sets a value for FCOJ. The speculative activity of the futures market provides the finance needed to transact commercial hedges and set price levels. In addition to long-term contracts there is also a spot market for FCOJ.

Quite large differences in import duties for orange juice exist between importing countries. As regards the consumption of orange juice, the US and Europe are the largest markets.

3.1 The chain of supply

There are many links in the supply chain for orange juice – from ripe oranges ready for picking to the consumer opening a carton of juice at a faraway location (see Figure 3.1). The product usually changes hands several times en route. It is thus important to be familiar with the full sequence of juice production to understand the commercial conditions for each type of company that operates in the supply chain.

This section refers generally to orange juice production in Florida and Brazil, the two regions that dominate the world juice market.

Industry structure

Full vertical integration – where one company has all the steps in the production chain, from fruit harvesting to distribution of packaged consumer product, under a single roof – is rare in the orange juice industry. This is due not only to geographical factors but also to the way the industry has matured.

There is a trend for each link in the production chain – growers, fruit processors, juice packers and retailers – to become independent businesses. This may be a natural consequence of the marketplace demanding increased and specialized competence at each step of the production sequence. It may also be partly due to commercial factors, such as long-term supply contracts and the futures market, which allow enterprises operating in the citrus industry to reduce their commercial risk from market price fluctuations.

3.1.1 Growers

Orange growers manage the groves and harvest and sell the orange fruit. They range from small independent growers selling their fruit to a fruit handler or through a cooperative, to growers who are part of a large fruit processing company.

For the fruit processor, it is essential to secure a continuous supply of oranges in sufficient quantities and at the right price. Traditionally, many orange processors have owned the groves that supply them with all or most of the fruit they need during a season. Ownership is particularly important during periods of uncertain fruit supply and unstable prices, as during the Florida freezes in the 1980s. Today, however, fruit processors rely to a large degree on long-term supply agreements and alliances rather than ownership. Independent orange growers look to alternative outlets such as the fresh fruit market to preserve their profit margins in times of depressed concentrate prices.

The orange-growing and processing industry changes constantly in line with evolving commercial and political conditions. On the growers’ side, Florida has seen a shift from independent farmers to diversified agribusinesses that are proactive in marketing and seek long-term business relationships.

During the 1990s, growers in Florida divested juice production capacity. Processors that had until then owned their own groves formed partnerships with growers.

In Brazil, the large orange processors source an important part of their fruit (up to 50%) from their own groves. The remaining fruit mostly comes from long-term contracts with medium-sized and large growers. Today’s extensive grove husbandry methods and tree plantings that are needed to keep orange fruit diseases at bay demand substantial investment, which large growers are more likely to be able to afford. In Brazil, some 120 growers (or 2% of all orange farmers) produce almost 50% of the country’s orange crop. Recent years have seen small growers shifting to other produce, such as sugar cane or other types of fruit.

How growers are paid

Fruit quantities are often quoted in “field box” units. Based on Florida practice, one box is defined as 90 lb (40.8 kg) of oranges.

In Florida, payment to growers is not based on the weight of delivered fruit but on the soluble solids (juice sugars) obtained from the fruit. The quantity of soluble solids is calculated from the volume of juice extracted from the fruit multiplied by the °Brix level of the juice. The amount of extracted juice is determined by squeezing a sample of oranges on a “State test extractor”. Oranges rejected during screening at the processing plant’s fruit reception area are not paid for.

In Brazil, payment to the growers is based on the delivered fruit quantity. Traditional contracts tied to FCOJ world market prices have been replaced by freely negotiated contracts that take account of fruit quality. Still, fruit availability has a major impact on the rates that growers command. The 2016 fruit shortage raised prices from 14 reais/box in early contracts to 26 reais/ box late in the year.

3.1.2 Types of fruit processors

In short, orange processors take in fruit and process it to produce concentrate and NFC. They can be divided into two groups:

- Marketing processors

- Bulk processors

Marketing processors sell packaged juice under their own brand name, which requires retail and consumer marketing skills.

Bulk processors mainly sell their products in bulk form, which requires skills in the efficient distribution and marketing of a commodity.

The largest marketing processors are based in Florida and include Tropicana (part of PepsiCo group), and Citrus World. These companies process fruit into juice and fill it into retail packages at their own facilities. They also purchase additional juice in bulk form from other bulk processors.

For marketing processors, control of product availability is regarded as more important than ownership of manufacturing assets. As an example, Coca-Cola now focuses on marketing and distributing Minute-Maid and Simply Orange brands; Brazilian company Cutrale owns and operates the juice production facilities.

Bulk processors produce the majority of orange juice worldwide. Bulk delivery is the priority for the large Brazilian processors. They do not have their own consumer brands, partly to avoid competing with their bulk juice customers.

The last decade has seen major changes in Brazil’s orange juice industry, with a reduction in the major players from five to three. In 2004 Cargill divested its processing plants to industry leaders Cutrale and Citrusuco. In 2011 the latter merged with Citrovita and the new enlarged entity, called Citrusuco, is now the largest processor ahead of Cutrale and Louis Dreyfus.

Bulk products are transported in ship tankers, tank cars or in individual containers, such as 200 litre (55 gallon) steel drums and 1-tonne bag-in-box containers. Efficient transport is crucial for these commodity products. (See also Section 6.)

Several terminal installations around the world are dedicated to receiving and shipping frozen concentrated orange juice (FCOJ) using tankers. The larger Brazilian processors own terminals in Brazil for exporting bulk products and terminals in Europe, the US and Japan for importing FCOJ. These companies also own several large tanker ships designed and dedicated to transporting FCOJ. Since the early 2000s they also operate specially designed bulk ships and terminals for handling chilled aseptic NFC.

Bulk processors make their money from the difference between bulk concentrate prices and fruit prices – the bulk processing margin. Florida bulk processors are very vulnerable to the wide fluctuations in FCOJ prices and therefore they need to use the protections offered by the commodity trading market in a similar way to their Brazilian counterparts.

The links between Florida and Brazil strengthened during the 1990s. The major Brazilian bulk processors acquired several juice facilities in Florida and together account for about half of Florida’s juice production. Operating in both markets offers benefits such as higher trading efficiency and more options for balancing concentrate quality.

NFC, which has enjoyed strong growth in Florida and now accounts for more than 60% of processed fruit, offers superior margins to FCOJ for Florida juice producers. Bulk processors supply NFC to juice packers and marketing processors, but some also co-pack in their own facilities.

Brazilian processors are also shifting to increased NFC bulk production, both for overseas export and to meet the growing demand in the Brazilian and South American markets. Today, about 20% of oranges are processed into NFC.

Figure 3.3 shows the different routes that orange juice products take from bulk suppliers.

3.1.3 Blending houses

Consistent quality between batches of FCOJ cannot be maintained during processing. Variations in flavour profile, Brix/acid ratio and pulp levels are unavoidable because fruit varies during the season and operating conditions change in the plant. Juice packers, however, need to buy raw juice of defined quality as they, in turn, need to supply the market with uniform products over the long term.

The need for consistent juice quality has led to the emergence of “blending houses”. Blending houses process many different fruit juices, among which orange juice is a primary product. Their role is to provide juice packers with a concentrate (and sometimes also NFC) that consistently meets defined quality specifications. They achieve this by blending concentrates of different origin and adding flavour fractions, often according to customer-specific recipes. In addition to supplying the defined juice product, blending houses normally have specialist product know-how that they make available to their customers. (Blending house operations are also discussed in section 6.)

Blending houses are often located in or near the main entry ports for juice concentrate. Large Brazilian processors that have their own terminal facilities also offer blending house operations. The preparation of soft drink bases is another important business activity of blending houses that have developed from flavour-manufacturing operations.

Purchasing concentrate from a blending house is generally more expensive than buying it on the spot market. However, buyers can be assured of product quality that meets their demands.

3.1.4 Juice packers

Juice packers take in bulk product, treat it as required and then pack it in consumer packages. The juice packer may also control the distribution of the packaged product. Juice packer operations are described in more detail in section 7.

As with fruit processors, juice packers come in two main categories: those that market their own brands and those that focus on co-packing, for example for private label brands. Juice packers’ products may include nectars and fruit-based still drinks, as well as 100% pure juices.

Fluctuations in FCOJ world market prices are not always reflected in retail prices and may put pressure on juice packers. For a successful operation, the juice packer requires important skills in several areas:

Sourcing: raw material costs constitute a major share of the total cost. The right juice quality and favourable contracts are vital to overall profitability.

Processing/packaging: here the focus is on maintaining product quality and keeping running costs, including product losses, low.

Distribution: distribution of packaged product also accounts for a significant share of total cost, and efficient distribution therefore plays an important part in overall profitability.

Marketing: skills in this area are important to packers that market their own brands as well as those who focus on co-packing.

3.1.5 Soft drink producers

Although the term soft drinks strictly covers all non-alcoholic beverages, soft drink producers are commonly considered to be manufacturers of retail packaged carbonated beverages and fruit-flavoured still drinks.

A soft drink producer may use orange concentrate as a raw material, but will often purchase a prepared base from a blending house. FCOJ lacks sufficient flavour to produce drinks of low fruit content and requires enhancement with additional flavours. The solids from pulp wash are another juice ingredient often used in drink bases. So is core wash, as it provides effective cloud and can replace synthetic clouding agents in cloudy drinks. Emulsifiers and preservatives may also be present in the soft drink base. The soft drink producer needs only to add sugar or sweeteners, acid and water (plus carbonation as required) to a ready-prepared base.

Soft drink production is dominated by a few large multinationals and numerous local companies. Blending house specialists may provide a valuable source of experience and product knowledge for small to medium-sized soft drink producers, as they do for juice packers. Blending houses may also help in developing new soft drink products and in responding to new consumer trends.

3.2 World market pricing for bulk juice products

World market prices for FCOJ have fluctuated substantially over the years. A general correlation exists between FCOJ price levels and expected supply. In the past, market overreaction has caused very large price swings, which are usually undesirable for suppliers and juice purchasers alike.

Adverse climate events that reduce orange harvests can trigger sharp increases in orange concentrate prices. Such events include the Florida freezes in the 1980s and a severe drought in Brazil in 1994. During this period, orange juice consumption – and hence supply requirements – grew steadily. Even so, a cold summer in Europe that resulted in large FCOJ stocks followed by a good crop season would depress FCOJ to as low as USD 700 per tonne in the 1990s.

In the 2000s diseases and unfavourable weather conditions have caused a general decline in orange supplies, shifting concentrate prices upwards. From 2010 to 2013, FCOJ contracts hovered around USD 2,500 per tonne. But a continued fall in demand, due to the decline in global orange juice consumption, pushed FCOJ prices below USD 2,000 tonne. That said, the impact of the citrus greening disease, which drastically reduced recent Florida crops, will likely lead to higher prices in future.

Western Europe is the largest orange juice import market. Most imported FCOJ is unloaded at ports in Belgium and the Netherlands, and Rotterdam is typically the reference location for Brazil FCOJ world market prices, which are quoted in USD per tonne. Commercial terms specify the extent to which bulk shipping and other freight costs are included. A common example is free carrier (FCA) warehouse Rotterdam, which means that the price includes freight charges to Rotterdam and the loading of product onto road tankers. However, the price excludes import duty and transport costs from the suppliers’ storage facility – usually in the port area – to the user.

Unlike Brazilian concentrate, Florida FCOJ prices are stated in USD per pound solids. The delivery terms are usually free on-board carrier (FOB) in Florida. Hence the bulk price includes loading FCOJ onto, for example, a road tanker but not the costs of overseas transport. However, this is not normally required as the main market is North America.

FCOJ world market prices are set in US dollars. Variations in the Brazilian real against the dollar influence the margins of Brazilian processors. For European markets, the euro/dollar exchange rate influences retail juice prices. Figure 3.4 shows export prices for Brazil FCOJ delivered to Rotterdam, inclusive of freight costs (CFR – cost & freight).

Although weather conditions will have seasonal effects on crops, the long-term outlook for orange juice supply – and, by extension concentrate prices – hinges on the development of effective remedies for diseases such as citrus greening.

3.3 FCOJ commodity trading and the futures market

Buying and selling FCOJ evolved into commodity trading during the latter part of the 20th century. The spearheads of this shift were Louis Dreyfus and Cargill, two international commodity trading companies that were active in many fields besides citrus and also at the time among the largest Brazilian bulk juice producers. (Cargill divested its citrus assets in 2004.)

Commodity products are usually supplied in defined units and can be traded on the futures market. Futures are contracts agreed for the future delivery of a physical commodity, such as FCOJ. Cash price is the price at which the actual commodity sells for.

RISK MANAGEMENT AND PRICE SETTING

The futures market provides a means of managing risk for the citrus industry by hedging (protecting against financial loss) risk exposure caused by fluctuations in cash prices for products. Futures markets require the participation of both hedgers (risk shifters) and speculators (risk assumers). Hedgers are those in the citrus industry, such as fruit processors and sellers, who transfer unwanted risks associated with their normal commercial activities. Speculators (non-producers/ processors) seek financial gain by correctly predicting changes in future price moves. This speculative activity provides the finance required to carry out commercial hedges. In addition to risk shifting, the futures markets also sets the value for one pound of FCOJ solids, known as price discovery.

Trading of FCOJ futures began in the 1960s through the Citrus Associates of the New York Cotton Exchange (NYCE). The NYCE was integrated into the New York.

Board of Trade (NYBOT) in 2004. A few years later, Intercontinental Exchange acquired NYBOT and FCOJ futures and options are now traded through ICE Futures US. The physical trading floor remains in New York City. The regulations governing all transactions define quantities of FCOJ to be contracted and the time periods allowed for trade and delivery of contracts (every other month). The regulations also specify grade standards for product quality and product identification and inspection.

In 2004, a new form of futures contract was introduced that recognized the Florida/Brazil origin of FCOJ in order to track cash market transactions more accurately. These tend to value FCOJ from Florida and Brazil differently compared to other origins. Mexico and Costa Rica were later added to countries of origin in futures contracts.

The futures market is important to the citrus industry, not only as a tool for risk management but also as a price basis for purchasing fruit and for sales contracts for bulk concentrate.

Bulk juice processors earn their profit from the price difference between the fruit and concentrate. They must therefore be skilled in commodity product marketing and risk management.

In addition to long-term sales contracts, a spot market also exists for FCOJ, with delivery from tank storage and in drums. Spot market trade is high when price levels are unstable.

Spot market products may be of reduced product specification and thus command lower prices. During periods when orange juice retail prices are depressed, juice packers may be forced to acquire large volumes of such juice on the spot market.

3.4 Important duties and juice imports

Various trade negotiations have taken place in the past to try to reduce trade barriers and promote freer trade, including for citrus products. The General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT) secured major agricultural agreements in the Uruguay round of talks held in 1994. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) reduced trade barriers between the US, Canada and Mexico when it was signed in 1994. Trade tariffs between the three countries were gradually phased out before being fully eliminated in 2008. CAFTA-DR, a free trade agreement between the US and six Central American countries, entered force in 2006.

On the world market, frozen concentrates of Brazilian and other origin are usually traded per metric tonne product, with prices given as USD/tonne concentrate. In the US, however, the basic unit for pricing orange fruit, single-strength juice and FCOJ is the content of soluble solids (in principle the sugars), not the weight or volume of product. The unit used is pound (lb) soluble solids. The US futures market also uses pound soluble solids to define product quantity.

The following approximate factors can be used when converting prices:

For FCOJ of 66 °Bx

1,000 USD/t conc. = 0.70 USD/lb solids

1,430 USD/t conc. = 1.0 USD/lb solids

For NFC juice of 11.8 °Bx

1,000 USD/t juice = 3.82 USD/lb solids

260 USD/t juice = 1.0 USD/lb solids

Ad valorem tariffs

Duty calculated as a percentage of the value of the imported product. Freight costs are included in the product value

Specific tariffs

A duty of a fixed amount of money per unit of juice independent of its value

Quota

Defined maximum quantity of product allowed, for example at a lower import duty

SSE or single-strength equivalent

FCOJ calculated as the volume of juice it would yield when reconstituted to single-strength juice

GATT

General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs

NAFTA

North American Free Trade Agreement

For orange juice, substantial differences exist in import duties between the various importing nations. Duties often depend on the export country. Several have agreements with import countries that reduce or eliminate import tariffs. However, such specific agreements do not generally apply to the major exporters, Brazil and the US. All trade agreements are available from the World Trade Organization (WTO). When the WTO was established in 1995, it assumed responsibility from GATT for overseeing international trade rules.

US import tariffs distinguish between FCOJ and NFC, charging a higher rate for concentrated juice. The current (2017) duty rate is USD 7.85 per 100 litres SSE on FCOJ imported from Brazil and other countries in the normal trade relations (NTR) category. The corresponding duty rate for NFC is USD 4.5 per 100 litres SSE. Imports of FCOJ and NFC to the US from Mexico are duty-free under the terms of NAFTA.

The US applies a “duty drawback” procedure that favours the export of juice from the US. The procedure allows importers or exporters to recover the import duty paid for a certain volume of juice if they export the same volume and kind of product.

Tariffs for orange juice imported into the European Union vary greatly depending on the exporting country. The dominant share of juice imported into Europe comes from Brazil and is subject to “most favoured nation” (MFN) import duties. EU import duties are ad valorem and currently 15.2% for FCOJ and 12.2% for juices of less than 20°Brix.

The EU is the largest juice import market, followed by the US. The relative sizes of the major juice import markets are shown in Figure 3.5. The consumption of packaged orange juice per region is shown in Figure 3.6.

3.5 Global orange juice consumption

North American and European markets are the largest consumers of orange juice. The US and Canada account for some 40% of total global consumption of packaged orange juice, whereas Europe consumes about 35% of the total volume.

World orange juice consumption grew constantly during the last century, in particular during the 1980s and 1990s. This high growth was supported by increased production capacity, primarily in Brazil, and high output prevented price hikes. But overall consumption has declined since peaking in about 2000. A major factor is that US consumers, the largest market, drink less orange juice. This decrease has not been compensated by growth in emerging markets, such as China.

In the US, orange juice consumption was about 2.8 billion litres in 2016, far below the 5 billion litres drunk in 2001. The decline reflects changes in eating habits (more people skip breakfast), dietary concerns and higher retail prices due to citrus disease in Florida, which has curtailed juice production. Meanwhile, the shift in market share for the three main types of orange juice in the US market – frozen concentrate for home dilution, ready-to-drink (RTD) juice made from concentrate, and NFC – remains ongoing.

Frozen concentrate has steadily decreased from a dominant position to less than 5% of total orange juice retail sales. NFC, which emerged on the US orange juice market in the mid-1980s, has steadily gained a market share that now exceeds 60%. RTD juice made from concentrate accounts for about 35%. Virtually all RTD orange juice in the US is distributed refrigerated (4°C). See also section 10.3 and Figure 10.10.

In Europe, nearly all retail orange juice is RTD; there is very little concentrate. Total orange juice volume in Europe in 2016 was about 2.5 billion litres. Europe saw rapid growth of orange juice consumption in the 1980s and 90s (with a near-doubling from 1983 to 1993), but consumption has been in gradual decline since the turn of the millennium. Western Europe predominates, but Eastern Europe’s share of total juice consumption is increasing.

Most orange juice in Europe is made from concentrate. But consumption of NFC has increased in the last decade and now accounts for about 25% of total orange juice sales. Growth in per capita income and the perception that NFC quality rivals that of fresh fruit have driven the increase in NFC sales despite a high price premium. Indeed, NFC retails at up to double the price of orange juice made from concentrate.

Importing NFC into Europe is, however, significantly more expensive than importing FCOJ. This is due to NFC storage and shipping volumes being five to six times larger than for FCOJ, combined with the higher fruit quality standards required for NFC. Florida juice led the way when NFC was introduced to Europe, but today NFC is usually a blend of origins dominated by Brazil and Spain.

In other markets, South America – and especially Brazil – is experiencing rapid growth in the consumption of packaged orange juice. Some Far East markets such as Japan and South Korea have also shown large growth rates. However, juice consumption may fluctuate from year to year due to economic factors. In China, consumers generally prefer beverages with low juice content. However, demand for orange juice is growing in large cities in the fast-growing coastal regions.

Figure 3.6 shows consumption of packaged orange juice per region and Figure 3.7 shows consumption in the top 10 European markets.

3.6 Per capita orange juice consumption

The US remains the largest total consumer of orange juice worldwide, but per capita consumption – estimated at almost 9 litres per year – is no longer the highest. This position is held by the UK, with around 12 litres consumed per person. In the UK, orange juice accounts for the highest share of all fruit juices at more than 70%. Germany has the highest total fruit juice consumption in Europe. But because apple and blends are most the popular products, per capita orange juice consumption is much lower than in the UK. The per capita estimates in Figure 3.8 are based on a range of market data and refer to 100% orange juice.

The Florida Department of Citrus (FDOC) also estimates overall orange juice utilization in major markets. This is presumed consumption and is based on so-called “disappearance data”, or net utilization of bulk orange concentrate and NFC. It includes orange concentrate used to produce nectars and fruit drinks as orange juice consumption. The FDOC’s figures are therefore higher than the actual consumption of 100% juice only. However, they provide a valuable understanding of the total usage of processed orange juice in different markets. The FDOC estimates that the presumed consumption of orange juice in the US dropped from 20 litres per capita in 2000 to 10 litres in 2015 (single strength equivalents). Consumption reached its historic peak in the late 1990s. See also Figure 10.9.