The orange fruit and its products

In this chapter you will read about:

- The origin and spread of the orange plant from Southeast Asia to the rest of the world.

- Global orange production and the development of large-scale production.

- Common orange crop diseases and their control by using resistant rootstocks.

- The whys and wherefores of single-strength and concentrated juice.

- How the seasons are bridged to provide consumers with year-round supplies.

- What’s inside an orange.

- Nature’s gift: every part of the orange can be used for producing commercial products.

- Valuable by-products such as pulp, peel oil, essences and animal feed.

- The most important orange-growing regions.

Summary

The orange plant originated in Southeast Asia and spread gradually to other parts of the world. Today, orange juice products derive from four main groups of orange. About 70 million tonnes of oranges are produced globally per annum. Of this, around one third is processed into juice and the rest consumed as whole fruit.

Single-strength or concentrated

As juice is produced on a seasonal basis, it must be stored between seasons to ensure a year-round supply to consumer markets. Most juice is produced as frozen concentrated orange juice (FCOJ) because it can be stored for long periods of time and shipped at lower cost as it contains less water. “Not-from-concentrate” juice (NFC), which is single-strength, requires much larger volumes during storage and shipping. It is often intended for nearby markets, but infrastructure for overseas export of NFC is in place in major markets.

A look inside

Basically, an orange consists of juice vesicles surrounded by a waxy skin, the peel. The peel comprises a thin, coloured outer layer called the flavedo and a thicker, fibrous inner layer called the albedo. The endocarp, the edible portion of the fruit, includes a central fibrous core and individual segments containing the juice sacs. In large processing plants the complete fruit is utilized. By-products are produced to help maximize profits and minimize waste.

Major players

The two most important orange-processing regions are Brazil and the state of Florida in the US. Together these regions account for about 80% of global orange juice production.

1.1 The fruit’s origin and important varieties

The orange is the world’s most popular fruit. Like all citrus plants, the orange tree originated in the tropical regions of Asia. Oranges are mentioned in an old Chinese manuscript dating back to 2200 BC. The development of the Arab trade routes, the spread of Islam and the expansion of the Roman Empire led to the fruit being cultivated in other regions.

From its original habitat, the orange spread to India, the east coast of Africa, and thence to the eastern Mediterranean region. By the time Columbus and his followers took plants to the Americas, orange trees were common in the western Mediterranean region and the Canary Islands.

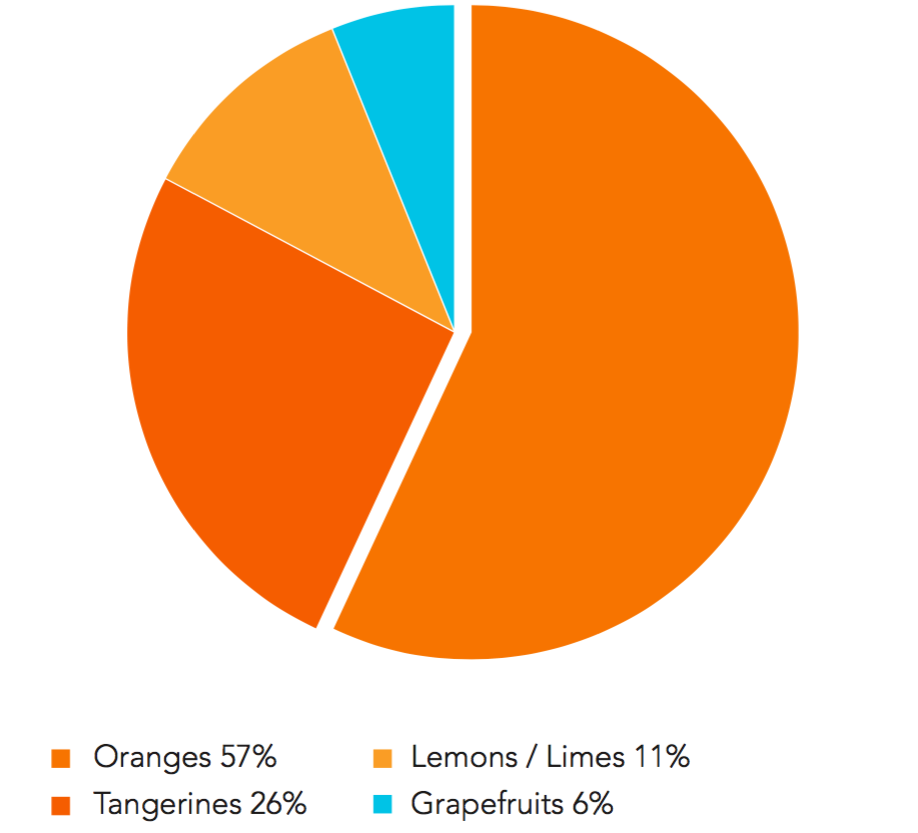

Oranges account for more than half of the world production of all citrus fruits, of which other important species are the lemon, grapefruit and mandarin (see Figure 1.1).

Four groups of fruit are of commercial significance in the production of orange juice products:

- The sweet orange, also known as the China orange, Citrus sinensis

- The sour or bitter orange, also known as the Seville orange, Citrus aurantium

- The mandarin orange and tangerine varieties,

- Citrus reticulata

- Hybrid oranges (tangors) that result from various crosses between tangerines and sweet oranges.

Of these, the sweet orange is by far the most important. In several markets, including Europe, only juice made from sweet orange varieties, Citrus sinensis, may be labelled as orange juice. To be correct from a horticultural perspective, the common name for the species Citrus reticulata is mandarin, some varieties of which are called tangerines. However, the word tangerine is often used as the common species name.

Most citrus plants are propagated vegetatively by bud wood cuttings (scions – the top part that controls the type of fruit) grafted on to a different rootstock. This means that trees of the same cultivar are genetically identical and respond similarly to their environment, for example fruit ripens at a similar time, which allows efficient harvesting and operation of processing plants. However, it also means that trees of the same variety in a grove are susceptible to the same diseases and physiological disorders. As required in different regions, bud wood may be grafted on to rootstocks known to be resistant to certain diseases or drought.

During their first few years of growth, orange trees do not bear fruit. But when they do, the yield per tree increases gradually until the trees reach maturity at about 10 years old.

1.2 A global overview

Oranges are cultivated in tropical and subtropical regions around the world. The trees can grow in a wide range of soil conditions, from extremely sandy to rather heavy clay loams, though they grow best in intermediate soil types.

Local growing conditions, such as climate, soil type and grove practices, have a major influence on the quality of fruit produced and on the extracted juice. An orange variety, for example Valencia, may have quite different properties depending on where in the world it is grown. The major orange-growing regions are shown in Figure 1.2.

Approximately 70 million tonnes of oranges are produced per year worldwide. About a third of the total tonnage is processed, the rest being consumed as fresh fruit. Whenever possible, growers prefer to sell oranges to the fresh fruit market as their price is normally higher than for fruit sold for processing into juice. In some countries this can lead to a significant variation in the amount of fruit processed from one year to another.

Florida and Brazil are the world’s largest juice-producing countries. Here, the majority of fruit harvested is processed because the orange varieties in these regions are grown for processing rather than for direct consumption.

Due to the planting of new trees, world orange production continued to increase into the early 2000s – mainly in Florida, Brazil and China. Orange production is also expected to increase further in other regions as a result of improved planting programmes, cultivation techniques and support to orange growers. Nevertheless, unwanted climatic effects like frost and storms, along with uncontrolled fruit tree diseases, could reduce crops and juice yields significantly. Recent years have seen notable fluctuations in world orange production, and since 2010 the global harvest has declined as a result of unfavourable weather and diseases in major production areas.

1.2.1 Large-scale development

Commercial cultivation of oranges intended for large-scale processing into fruit sections and juice began in Florida in the 1920s. In the late 1940s, frozen concentrated orange juice for home dilution was developed in the US. This led to rapid growth in orange juice consumption. As a result, orange cultivation and processing capacity in Florida grew rapidly.

However, severe frosts in Florida drastically reduced fruit yields and killed many trees during the 1960s, 70s and 80s. To guarantee the supply of orange juice for the US market, trees were planted and large processing plants were built for orange concentrate in Brazil. The first concentrate plant was built in Brazil in the early 1960’s and the large expansion in production capacity took place during the 1970s and 1980s. Orange processing in Brazil was pioneered by US companies.

In 1983 Brazil surpassed Florida as the world’s number one orange producer. However, new trees that were planted further south in Florida in areas less affected by frost allowed Florida’s orange production to rebound. Thus, in years with good yields the state was able to meet most of the US orange juice demand. However, a series of hurricanes and the appearance of the citrus greening disease in the mid-2000s again adversely affected Florida’s orange growers, reducing production to its lowest levels since the 1960s. New measures to mitigate the lethal citrus greening disease are required to restore production.

China has seen the fastest growth in citrus fruit production through the intensive planting of new trees and is today the world’s largest producer. Mandarins make up the majority of the citrus crop. Most oranges in China are consumed fresh, with only a small amount of fruit being processed. The Mediterranean is an important region for growing high-quality fruit. As more and more Mediterranean oranges are being eaten fresh, juice production is gradually declining in this region, with the exception of Spain.

Figure 1.3 shows the estimated world citrus fruit production and processing for the 2013-14 season.

1.2.2 Orange crop diseases

Like any other fruit trees, orange trees are susceptible to diseases. These may affect the leaves or fruit and even kill the trees. Because diseases have a large economic impact on the citrus industry, many orange-growing regions allocate substantial funding to research on citrus diseases and develop more resistant fruit cultivars and cultivation methods to limit their effects.

The characteristics of a disease will determine the appropriate response to control it. Control methods include the eradication of infected trees, chemical suppression of disease-transmitting insects, and using resistant rootstock for grafting. New trees should come from controlled nurseries where seedlings are protected from airborne or soil contamination.

The inspection of groves and follow-up of measures taken are important for successful control of a disease. Large eradication programmes may require special funding. An outbreak of citrus tristeza virus (CTV) killed almost all orange trees in Brazil in the 1940s. New plantings were made using a different rootstock (Rangpur Lime) resistant to this virus.

Among the serious citrus diseases found today is citrus canker, caused by Xanthomonas bacteria, which results in premature leaf and fruit drop. There is no treatment but the disease is restricted by elimination of infected groves and rigorous inspection programs. Spraying with copper during the budding period helps protect young trees against citrus canker. Copper applications are also beneficial in reducing symptoms of citrus black spot. This fungal disease causes lesions on the fruit skin that make fruit unsuitable for consumption though it can still be processed.

In the 1990s Brazilian citrus cultivations experienced a widespread infection of citrus chlorosis variegated (CVC), a disease leading to spotted leaves and small fruit. It is caused by a bacterial pathogen transmitted by the sharpshooter insect. Renewal of old infected trees and constructing enclosed nurseries for citrus seedlings have enabled CVC infection levels to be reduced to a few percent. At the time of writing (2016), Florida is free from CVC.

In 1999, a new disease was discovered in Brazil called citrus sudden death (CSD), so named because it caused the rapid decline and death of trees with fruit and leaves still on them. It is caused by an insect-transmitted virus (similar to tristeza) and spread in just a few years to important citrus areas of São Paulo State.

Certain rootstocks are resistant to the sudden death virus. Remedial measures focus either on replanting using resistant trees or in-arching. The latter is a method where resistant seedlings are planted next to an existing exposed tree and a bypass is grafted onto it above the bud union. However, the alternative rootstocks are less resistant to drought and require more irrigation facilities or be used to plant orchards in areas with a wetter climate.

The most severe disease yet to affect modern citrus plantations was detected in Brazil in 2004, and a year later in Florida. Huanglongbing (HLB), a deadly bacterial disease, is thought to originate from China where it was first reported a century ago. The causal pathogen is spread by an insect, the Asian citrus psyllid. After feeding on an infected plant, the psyllid injects the bacterium directly into the tree’s vascular (or food transportation) system, making access for treatment difficult.

Unlike in citrus sudden death disease, it may take several years before infected plants show HLB symptoms. The early signs are yellow leaves. With time, the infected trees yield small, misshapen fruits that fail to ripen. The juice from affected fruits is high in acids and has a bitter taste, making it undesirable. Since the mature fruits retain their green colour at the navel end, HLB is commonly called citrus greening disease.

There is no known cure for HLB. Current efforts to restrain the disease involve psyllid control, addition of nutrients to improve plant health, and removal of infected trees. Insect species that are natural enemies to psyllids are introduced into vulnerable areas alongside chemical pesticide treatments to help suppress psyllid populations.

Today citrus greening is present in many citrus-producing regions in Asia, Africa and Americas. It has demonstrated an ability to spread rapidly and cause large reductions in fruit yields; in Florida production has declined by 50% in the last 10 years. In China, some citrus cultivation has moved to cooler areas because lower temperatures reduce the impact of HLB (in its Asian version).

Intensive research on how to combat HLB is in progress, from adapted grove practices to advanced genetic research. The short-term aim is to find solutions that ensure tree (and industry) survival until new root stocks or citrus cultivars that are resistant to the lethal bacteria have been developed.

As orange crop diseases multiply, so do growers’ costs to keep them in check. In Florida, production costs per acre have nearly doubled from 2003 to 2015 due to extensive grove inspections, frequent insecticide treatments and increased tree replacement. Lower fruit yields from infected trees cut further into growers’ profitability.

Certain diseases may spread through fresh fruit shipments. To prevent this, regulations require growers to certify that fruit is free from quarantine diseases, such as citrus canker, citrus black spot or HLB.

1.3 Bridging the seasons

Oranges can only ripen on the tree, and the quality of the fruit begins to deteriorate immediately after picking. Therefore, the time between picking fruit and processing it into juice and other products should ideally be as short as possible – less than 24 hours – even if longer periods are not uncommon.

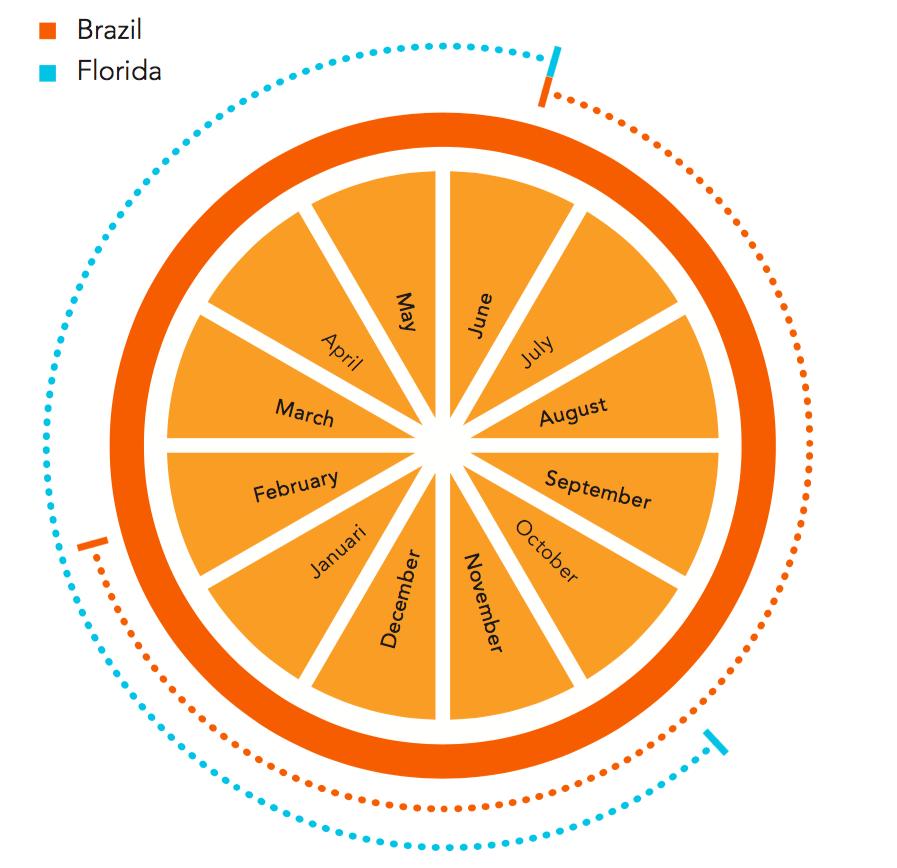

Because orange is a seasonal fruit, each region strives to grow orange varieties with different ripening periods (see Figure 1.4). This prolongs a region’s total harvesting period and allows greater utilization of processing equipment.

To provide a year-round supply to consumers, juice must be stored to bridge the gap between seasons. Most of the juice is stored frozen as concentrate. This is called frozen concentrated orange juice – or FCOJ as it is referred to within the industry. For the same amount of ready-to-drink (RTD) juice, concentrate requires 5–6 times less volume for storage and shipping than single-strength juice. Thus, shipping costs over long distances are significantly higher for single-strength products like not-from-concentrate juice (NFC).

Juices from early and late fruit varieties differ in quality as regards colour, sugar content, and so on. To deliver products of specified and consistent quality throughout the year, concentrate suppliers blend concentrates produced from different orange varieties. Most NFC products also consist of a blend of juices extracted at different times of the season. NFC blending may take place within the producing country or in the importing market. The difference in quality and yield between orange varieties is reflected in the range of market prices.

1.4 Fruit selection

In Brazil, the typical processing season is from June to February. In Florida, oranges are usually processed from October to June. Good quality fruit is harvested for the greater part of the season. In the Mediterranean, the period yielding fruit of quality suitable for processing is shorter than in Florida and Brazil.

NFC is essentially juice as it is extracted directly from the fruit. Regulations and the production process allow for very limited, if any, adjustments to product characteristics other than blending NFC from different varieties. Careful selection of the fruit is therefore necessary for NFC production. In concentrate production, it is possible to adjust certain quality parameters. Careful control of the evaporation step, essence recovery and the possibility of blending concentrates that differ in character enable the processor to meet many different product specifications. Hence, variations in fruit properties are less critical for concentrate production.

In plants where NFC is produced, concentrate should also be produced to make use of “non-optimal” fruit. In most regions, fruit best suited to NFC production is available for only part of the season. The proportion of NFC and concentrate produced in a certain region will depend on the availability of suitable fruit.

At present, NFC production makes up a minor part of the total juice production in most orange-growing regions except for Florida, where the share of NFC production reaches 60% or more.

ABBREVIATIONS AND DEFINITIONS

FCOJ

Frozen concentrated orange juice

NFC

Not-from-concentrate juice

Single strength

The natural strength of juice and that at which it is consumed.

Single-strength equivalent (SSE)

Concentrate and other products stated as their corresponding amount of single-strength juice

With oranges grown to be eaten fresh, a certain amount of fruit is rejected because of poor appearance (up to 20%). The rejected fruit is used for processing into juice. This is why juice processing facilities are also found in regions that specialize in producing oranges intended for the fresh fruit market.

1.5 Inside an orange

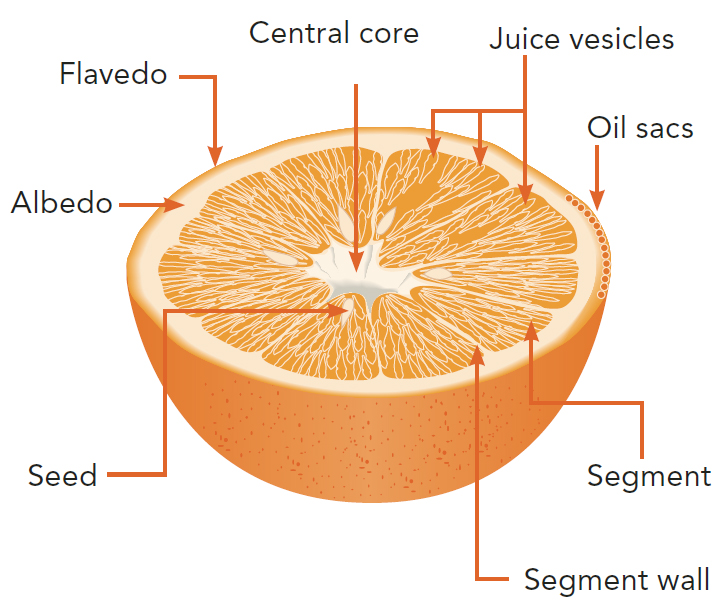

Essentially, an orange is a ball of juice sacs protected by a waxy skin, the peel. The peel consists of a thin outer layer called the flavedo and a thicker, fibrous inner layer called the albedo. Orange-coloured substances called carotenoids in the flavedo give the fruit its characteristic colour. Vesicles (small sacs or cavities) containing peel oil also present in the flavedo contribute to the fruit’s fresh aroma. The white spongy albedo contains several substances which influence juice quality, often negatively, if they find their way into extracted juice. These substances include flavonoids, d-limonene, limonin and pectin.

The edible portion of the fruit is known as the endocarp. It consists of a central fibrous core, individual segments, segments walls and an outer membrane. The segments contain juice vesicles, or juice sacs, that are held together by a waxy substance. Seeds may also be present within the segments. (See Figure 1.5).

Apart from the juice itself, droplets of juice oil and lipid are also present in the juice vesicles. The juice contains sugars, acids, vitamins, minerals, pectins and coloured compounds, along with many other components. These are discussed in more detail in subsection 2.2.

After juice is extracted, fragmented juice sacs and segment walls are recovered as pulp. When these particles are large, they are referred to as floating pulp because they rise to the juice surface. Very fine particles and suspended solids that gradually accumulate at the bottom of the juice are called sinking pulp.

1.6 Squeezing out every drop

In theory, the aim of the juice extraction process is to remove the maximum amount of juice from the fruit without including any peel. In practice, a compromise is made between the possible juice yield and the desired product quality. The maximum juice yield from an orange is 40–60% by weight depending on the fruit variety and local climate. Valuable oil from the peel is recovered during juice extraction. Volatile flavours from the juice are also recovered during juice processing. The remaining material is mainly pulp, peel, rag and seeds. Some pulp is recovered for sale as a commercial product. Soluble solids are reclaimed from the remaining pulp stream by washing with water. d-Limonene is extracted from oil in waste peel for use in the chemical and electronics industry. Other by-products such as pectin and clouding agents are sometimes recovered. Peel and other residual waste can be dewatered and dried as pellets for animal feed. Because orange waste is highly biodegradable, small plants may dispose of it as landfill.

Increased cost-efficiency is important for the orange juice industry. Equipment development for citrus processing is aimed at increasing juice yields while maintaining juice quality. It is also very important to reduce energy and water usage at the fruit processing plant as well as to further refine by-products and find new uses for them.

1.7 Primary and secondary products

The orange is one of nature’s gifts. Its two primary products – whole fruit and juice – are enjoyed worldwide. Various secondary products – the by-products – help to maximize profits and minimize waste. No part of the fruit is unused after juice extraction provided that fruit throughput justifies investment in equipment that can turn pulp and peel into commercial products.

A range of products that can be obtained from oranges is summarised below. Many are discussed in greater detail in other sections of this book. Yields of the various products derived from Florida Valencia oranges are shown in Figure 1.6.

Fresh fruit

After picking, fruit intended for the fresh fruit market is sent to packing stations, where it is normally graded by visual inspection, washed, coated with wax and packed. The detergent used in washing may include fungicides. As traces of fungicide could find their way into the juice during extraction, several import markets prohibit the processing of fruit from packing houses into juice.

Juice

This product is produced in two alternative ways:

- As a single-strength (natural strength) bulk product in frozen or aseptic form (NFC)

- As bulk concentrate normally frozen (FCOJ)

Comminuted citrus base

A by-product made either by milling the whole fresh fruit or by mixing juice concentrate with milled peel. This product is used as an ingredient for fruit drinks. Because comminuted citrus base has a stronger flavour and provides more cloud than pure orange juice, it imparts a good orange flavour to fruit drinks of low fruit content. It was originally developed in the UK.

Pulp

This is ruptured juice sacs and segment walls recovered after the extraction process. It can be added back to juice and juice drinks to provide mouthfeel and give a natural appearance to the product. Pulp, also traded as “cells”, is usually distributed frozen but also in aseptic bag-in-box containers.

Pulp wash

A product reclaimed from washing the pulp stream. Pulp wash contains soluble fruit solids and is often used in fruit drink formulations as a source of sugars and fruit solids. It is also used as a clouding agent to provide body and mouthfeel because of its pectin content. If permitted by law, pulp wash is sometimes added to juice in-line before concentration. Pulp wash is also referred to as water-extracted soluble orange solids (WESOS).

Peel oil (cold-pressed oil)

The oil extracted from orange peel. Some peel oil is added to concentrate after evaporation prior to long-term storage. It masks or slows the development of a cardboard off-taste during storage. Peel oil is sometimes used by blending houses and juice packers for extra additions to concentrate. It is sold to flavour manufacturers for the production of various flavour compounds used in the beverage, cosmetics and chemical industries. In trading, it is often referred to as cold-pressed oil (CPO) or cold-pressed peel oil (CPPO).

Essence

Essence comprises the volatile components recovered from the evaporation process. These are separated in an aqueous phase and an oil phase. The water-soluble compounds (essence aroma or water phase essence) are sometimes added back to the concentrate or juice product. The oil phase (essence oil) is different from peel oil and contains more of the fruit flavour. Essence oil is also used as add-back to concentrate. Both aroma and essence oil are raw materials used by flavour companies for the manufacture of flavour mixtures for the beverage and other food industries.

Core wash

A liquid recovered by washing the core material ejected from the JBT juice extractors. This rag and seed material is very high in limonin. If the resulting core wash is too bitter it may pass through a debittering process, keeping its other characteristics similar to pulp wash. It is concentrated and used as a flavour component and clouding agent in beverage formulations.

d-limonene

The major component of peel oil. Industrial d-limonene is recovered as a by-product from waste peel in the feed mill. It is sold for use in the plastics industry as a raw material in the manufacture of synthetic resins and adhesives. It has also found use as a solvent, for instance in the electronics industry.

Animal feed

Dry pellets made from the material left over from juice processing. The waste stream consists of peel, rag, unrecovered pulp and seeds. This residue is dewatered and dried to form concentrated fodder for cattle and sheep.

Citrus molasses

The syrup produced from the concentration of liquor pressed from the wet waste stream. It is used in producing animal feed pellets or as raw material for the production of citrus alcohol by fermentation.

Pectin

A less common by-product of fruit peel. Pectin can be extracted from the peel for use in jam, marmalade, jelly and preserve production.

1.8 Major orange-producing regions

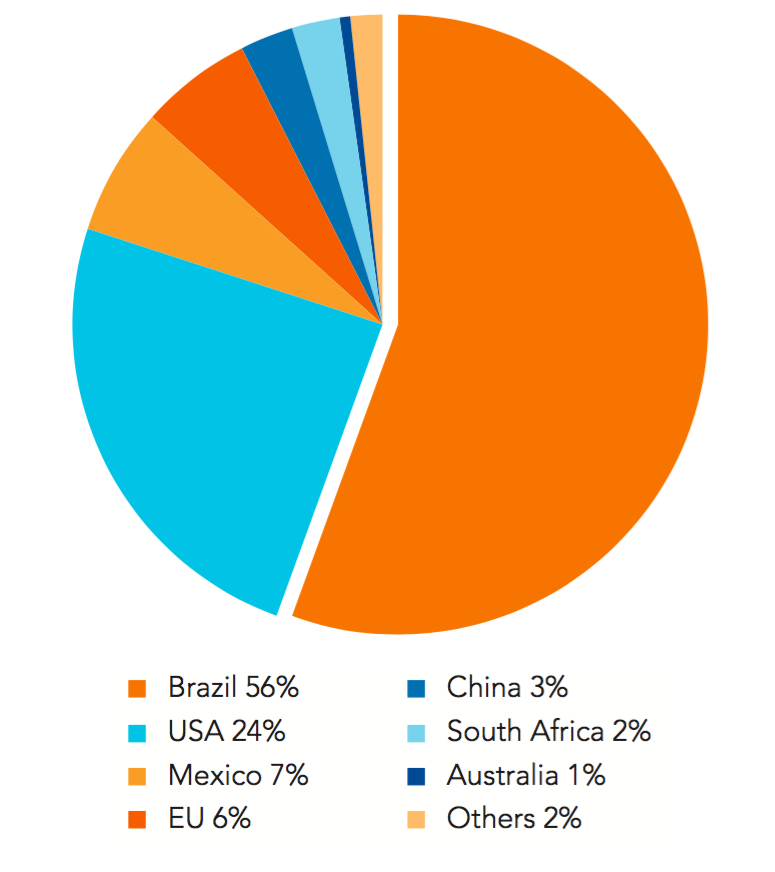

Together, Brazil and the US grow one third of the world’s oranges but produce about 80% of the global orange juice supply (10 billion litres/year). Regions contributing to the majority of world orange juice production are shown in Figure 1.7.

The world orange juice export market is dominated by Brazil. American exports are quite small due to the large US domestic market for orange juice. (See Figure 1.8).

In the past, the US was a significant net importer of juice. However, increased juice production in Florida in the 1990s following new tree planting caused national net juice imports to decline. Although the Florida harvests have again decreased, a concurrent fall in domestic juice consumption has kept US imports at 5-10% of global juice imports. Figure 1.9 shows orange juice production in Brazil and Florida between 2008 and 2015.

1.8.1 Brazil

During the 2015/16 season, the orange crop in Brazil was about 14 million tonnes (350 million boxes of 40.8 kg/90 lb). Most commercial groves and processing plants are located in the state of São Paulo and western Minas Gerais, where 250 million boxes were produced. The 2015/16 harvest saw a 20% drop in fruit yield from the previous season as higher than normal temperatures significantly damaged fruit setting. Low fruit availability and processing yields resulted in the lowest juice production for 20 years. Forecasts for the 2016/17 season project a sharp production increase, based on expected larger fruit crops and average industrial yields.

The majority of Brazilian oranges go to processing. However, the share of fruit sold in the domestic fresh fruit market is increasing thanks to rising per capita income.

Brazilian oranges tend to be smaller, less round and have thicker peel than those grown for processing in, for example, Florida. The normal processing season for Brazilian juice plants is from June through to early February. More than half of the plantings are late varieties (Valencia and Natal). However, the shares of early (Hamlin) and mid-season (Pera Rio) fruit are each increasing beyond 20% among new trees.

Groves are not normally irrigated (less than 30%) and climatic variations, including drought, can have a strong influence on fruit yield and juice quality. Some citrus varieties (Hamlin and Valencia) have a biennial cycle that leads to additional cyclic fluctuations in orange output. The variation in yield per tree obtained during recent harvest seasons is shown in Figure 1.10.

In Brazil, the “bloom” – the time when the tree flowers and is pollinated before the new crop of fruit starts to grow – does not occur at the same time for all the trees in a grove or plantation. As a consequence, trees in a grove bear fruit of differing ripeness at any given time.

THE BRAZILIAN ORANGE CROP

Sweet oranges comprise the bulk of the Brazilian crop. The most important varieties and their harvesting seasons are:

| Hamlin | June to August |

| Pera Rio | June to mid-July, |

| mid-August to mid-December | |

| Natal | September to mid-January |

| Valencia | mid-July to September, |

| mid-October to January |

Since fruit in a specific grove is gathered at one picking, the harvested crop will vary in maturity. This variation in fruit ripeness forces the processor to make compromises in the juice extraction process that affect both the quality and yield of juice produced. Nevertheless, the processor can modify process conditions and use essence recovery and juice blending to compensate for variations in fruit to produce juice concentrate of consistent uniformity.

Most juice in Brazil is processed into concentrate that is exported in large volumes. But NFC production has increased steadily since the 1990s and now absorbs around 20% of processed oranges. It is sold domestically and exported to North America and Europe.

1.8.2 Florida

During the 2014/15 season, the Florida orange crop was only about 4 million tonnes (97 million boxes), the lowest level for 50 years. Back-to-back hurricanes in 2004 and 2005 severely reduced fruit yields, while the continued decline in orange production (see Fig. 1.11) is linked to the Huanglongbing citrus disease. A 2016 survey estimated that 80% of citrus trees were infected by this harmful bacterium. The removal of sick trees and abandonment of groves has seen the commercial tree inventory drop by a third since 2004. To reverse the decline and to ensure the recovery of the state’s citrus industry, effective measures to mitigate HLB are urgently needed (see section 1.2.2).

The Florida orange industry is focused on juice production: about 95% of the orange crop is processed into juice or juice products. A combination of climatic conditions, tree variety and soil conditions result in fruit that has a low appeal to the fresh fruit market but produces very high quality juice.

The skin is not uniform in colour and is often quite green or yellow. The peel is fairly difficult to remove, which can lead to consumer rejection. However, the round shape and thin peel of Florida oranges make them ideal for mechanical extraction systems.

THE FLORIDA ORANGE CROP

The main varieties and harvesting seasons of sweet oranges in Florida are:

| Hamlin | October to January |

| Parson Brown | October to January |

| Pineapple | December to March |

| Valencia | February to June |

During the early part of the season the orange juice is light in colour and has a low oil content. In late-season, the juice has a stronger colour and higher oil content. Some mandarin and hybrid fruit are also processed into juice from December to April for blending in small amounts with orange juice to obtain the desired colour and/or flavour.

Florida also produces around 15% of the world’s grapefruit, of which about half is processed into juices and fruit products.

The Florida orange juice processing season extends from October to late May/early June. Seasonal variations occur from year to year, depending on the weather.

The round shape and thin peel of Florida oranges make them ideal for mechanical dejuicing systems

Climatic conditions in Florida are such that the bloom occurs uniformly and during a very short period, usually two or three weeks. The high level of grove management includes irrigation and intensive pest and weed control. This combination of favourable climate and proficient grove management enables the fruit to ripen uniformly for efficient harvesting. Moreover, uniform fruit quality enables the processor to select the optimum processing conditions for the fruit harvested each day.

There has been a shift in orange processing away from FCOJ to NFC to meet the demand of the North American market. In years with lower orange yields, processing to NFC is favoured at the expense of FCOJ production. At present, 60% or more of the total orange crop goes to NFC production. Most NFC juice is consumed in the US. Distances between juice production and consumption are relatively short.

1.9 Other regions

California

California is the second largest orange-producing area in the US as regards fruit quantity and the leading supplier of oranges to the fresh fruit market. The state’s dry climate yields oranges with thick skin and a favourable appearance to consumers. California produced about 2 million tonnes of oranges during the 2015/16 season.

The dominant sweet orange variety in California is Navel, a seedless variety, followed by Valencia. Both are grown primarily for the fresh fruit market. About 20% of the crop, which for some reason is considered unattractive to consumers, is used for fruit processing.

Navel orange juice has the peculiarity of developing a bitter taste after processing. In small amounts, Navel juice can be used for blending with other juices or, alternatively, the bitterness can be removed in a debittering process.

Citrus growers in California are vigilant towards HLB, also known as the citrus greening disease. The psyllid vector is present in the state and infected plants have been identified in residential areas. However, as of the end of 2016 the disease had not been detected in commercial orange groves.

Other orange-growing states in the US are Arizona and Texas.

Mexico

During the 2014/15 season, Mexico produced 4.2 million tonnes of oranges, accounting for 60% of citrus production. Limes, with more than 30% of citrus production, hold second place and their plantation area is expanding. The sweet orange crop is dominated by the Valencia variety, and most of the fruit (about 65%) goes to the fresh fruit market for consumption as freshly squeezed juice.

Oranges are grown in several states. Veracruz is the largest producer, supplying 50% of the country’s total fruit. Orange-growing areas often experience a shortage of investment money and difficulty in achieving effective grove management. This leads to variations in crop size and fruit quality from year to year. HLB is a potential threat also to Mexican orange growers. The bacterium has been confirmed in vector insects in several states but has not yet directly impacted citrus harvests.

Production volume of FCOJ depends on world FCOJ market prices and raw material costs. In years with short orange supply, high prices in the domestic fresh fruit market result in less fruit going to processing.

Caribbean and Central America

This region includes several areas of small but increasing orange cultivation and orange juice production. Valencia is the most common variety of sweet orange. Grove management is not intensive and irrigation is rare. Climatic variations lead to differences in crop yield and juice quality between seasons. The main product in this region is frozen concentrate, although NFC is also produced for export markets.

Orange processing capacity has been consolidated in Belize and Costa Rica as well as in Cuba, which was the largest citrus producer in the region in the 1990s. However, production of oranges and grapefruit in Cuba is currently only a fraction of previous levels. This decline is due to a devastating hurricane in 2001 and deteriorating infrastructure.

Valencia oranges are harvested from December to June. Fruit harvested from March onwards tends to be high in sugar and low in acidity, which leads to very high Brix/acid ratios (>25). This juice therefore requires blending.

Argentina

Citrus production in Argentina was about 2.6 million tonnes in 2015/16. Oranges made up about 30% of the total crop, the main outlet being the fresh fruit market. However, lemons are the most important citrus crop. Argentina is the world’s largest producer, yielding about 1.4 million tonnes annually. The effects of severe frosts in recent years have been overcome by investment in new trees.

Most lemons are grown in the northeast province of Tucuman. The strategy of exporting only fruit of extra-high quality has resulted in sustained export price levels, albeit at lower volumes. Consequently, about 75% of the lemon crop is processed into juice. Local consumption of lemons is small, and the main export markets are Europe and Russia, with gradually expanding sales in Asian markets. Fresh fruit export to some regions has been constrained by required protocols and phytosanitary standards, but these demands are now being increasingly met.

China

China has seen the highest growth in citrus fruit production and in 2011 overtook Brazil to become the world’s largest producer. In the 2015/16 season about 32 million tonnes of citrus fruit was harvested across China, up 150% over 15 years. Nevertheless, fruit yields are relatively low compared to other large citrus-producing regions because of poor cultivar availability and grove practices. Recognising these deficiencies, the Ministry of Agriculture issued an action plan in 2014 to promote advances in farming and processing.

The main citrus growing areas are located in the country’s south-eastern regions. Jiangxi, Guangxi, Chongqing and Sichuan are the most important provinces for orange production along with Hubei and Hunan.

Mandarins account for the lion’s share of Chinese citrus – about 20 million tonnes in 2015/16. Virtually all goes to the domestic fresh fruit market, with only 3% canned. The remainder of the 2015/16 crop comprised close to 7 million tonnes of oranges and 4 million tonnes of pomelos. The sweet orange cultivars include Hamlin, Navel, Valencia, and Chinese varieties. Most oranges are consumed fresh; few are processed into juice.

At present, the majority of oranges are harvested during a short period. Since fruit quality deteriorates rapidly after harvesting, the fresh fruit consumption period is short at three to four months. By comparison, Brazil and Florida have typical harvesting cycles with balanced yields over seven months. There is a strong desire in China to change to fruit varieties that result in longer consumption and processing periods.

Imported fruits have gained acceptance following the rise in local crop prices and reduced import tariffs (since China joined the WTO in 2001). At the same time, consumers in the large cities expect to find oranges in the supermarket all year round, which creates a demand for counter-season imports. These are fulfilled primarily by South Africa, Australia and the US.

The overall utilization of orange juice is declining in China as the rapidly expanding market for juice-containing beverages lost momentum in 2014. Chinese consumers are generally not fond of 100% orange juice made from concentrate, but demand for NFC chilled orange juice is growing in top-tier cities, driven by cold-chain distribution and high disposable incomes.

Citrus greening disease, or HLB, was initially detected in China in 1919. Today it is widespread in the southern region of Jiangxi province, where several million trees have been uprooted. Some of the affected groves have been abandoned; others have been replanted with alternative citrus cultivars, such as pomelos. Since the impact of HLB is less in cooler regions, planting of new orange trees has shifted to cooler areas in, for example, Hunan and Hubei provinces.

Japan

Citrus fruit grown in Japan consists primarily of mandarin varieties, the most common being Unshu Mikan, a domestic traditional Satsuma cultivar. More recently “late harvest” mandarin varieties have been bred and introduced into citrus orchards to provide local fruit during the winter season. The production of Unshu Mikan peaked in 1975 at 3.7 million tonnes. Since then, plant acreage has gradually decreased and the current crop is below 1 million tonnes. Nevertheless, Unshu orange is the third most popular fresh fruit among Japanese consumers, behind apples and bananas.

Only a small proportion of Unshu fruit is processed into juice. The needs of Japan’s juice market are met by imported orange concentrates, mostly from Brazil (though trade agreements with lower tariffs favour imports from certain other countries such as Mexico).

Australia

Sweet orange varieties in Australia are Navel and Valencia. Navel’s high popularity in the fresh fruit market (it is easy to peel and enjoyable to eat) has spurred new plantings to replace old Valencia trees and now accounts for the majority of the crop. Australian orange production was about 0.5 million tonnes in the 2015/16 season.

More than 40% of the orange crop is exported. This reflects a drive to increase the export of fresh fruit, primarily Navel, to Far Eastern markets and, increasingly, the US. As Australia has an alternate season to the US, it can supply the American market with high-quality fruit during the California Navel off-season. Exports from Australia begin in June with early Navel varieties and end in October with late Navel oranges.

Fruit for processing, mainly Valencia, has decreased to less than 20% of the total harvest. Australian juice producers today favour NFC production because it is difficult for them to compete at world market prices for concentrate in the domestic market. Frozen concentrate, which makes up about half of the packaged juice market, is mainly imported from Brazil.

Mediterranean countries

In order of crop size, the most important orange-growing countries in the Mediterranean are Spain, Egypt, Italy, Turkey, Morocco, Greece, Syria and Tunisia. About 13 million tonnes of oranges are grown in this region (2013/14). This represents about 20% of world orange production, and about double the yield in Florida the same year.

Oranges in the Mediterranean region are primarily grown for the fresh fruit market, both domestic and for export to European countries. Only 10-15% of the regional crop goes for processing. The Mediterranean area is also important for other citrus fruits. Mandarin production is about 6.5 million tonnes, or 20% of world production. Lemon production of about 3 million tonnes accounts for 25% of world supply.

Spain is the largest Mediterranean producer of oranges and mandarins, and the global top exporting country for orange fruit. The most important sweet orange varieties in Spain are Navel and Valencia. Because exports to fresh fruit markets dominate, growers try to extend the supply periods by developing early and late cultivars. Production of orange concentrate has fallen drastically in Spain because production costs are not competitive with world-market concentrate prices. This is despite the fact that processors in European Union countries are entitled to a significant subsidy for purchasing fruit for juice production. NFC is produced from high-quality Valencia fruit for the growing European NFC market.

The cultivation of seedless clementines in Spain has met with success among consumers. Most fruit is exported and accounts for 60% of world mandarin exports As in Spain, orange concentrate production in Italy has dropped sharply because of strong international price competition. However, in Sicily several types of blood orange unique to the island are grown. Juice from these oranges has created a niche market for export of both NFC and concentrate. In other cultivation areas, replacement of blonde oranges with more profitable pink grapefruit is taking place.

Spain is the largest Mediterranean producer of oranges and mandarins

Israel

Israel’s local citrus industry helped to build the European juice market in the last century but has been in decline for many years. From orange harvests of more than 1 million tonnes in the 1980s, Israeli production has dropped to around 0.1 million tonnes. Growers today focus on easy-peeling mandarins and grapefruit, which together comprised 70% of the total citrus crop of 0.5 million tonnes in 2014/15 season. Red grapefruit and Or mandarins dominate also fresh fruit exports. Overall, the fall in fruit availability has caused the closure of processing plants, while uprooted orchards have given way to urbanization.

South Africa

South Africa has an expanding citrus industry and is currently the second largest exporter of citrus fruit after Spain. Most of the orange crop, some 1.7 million tonnes, is exported as fresh fruit. About a quarter is processed into juice and 5-10% goes to the domestic fresh fruit market. The main orange varieties are Valencia and Navel.

Traditionally, the main export market for orange fruit was Europe, but deregulation in 1997 opened up new opportunities that led to Asia and the Middle East becoming important markets. Export volumes of mandarins are expected to increase greatly in the coming years as a result of extensive new plantings; mandarin orchards nearly doubled in area between 2010 and 2015.

South Africa has good potential for exporting fresh fruit to the northern hemisphere because of its alternate season. However, successful trade depends on South Africa meeting the phytosanitary requirements and production protocols of the importing regions. Changes in the organization of the South Africa citrus industry have taken place aimed at enabling producers to meet importers’ demands more efficiently.