Packaging and storage of orange juice

In this chapter you will read about:

- The quality parameters that need protection during storage and what affects them.

- The role of oxygen in vitamin C degradation, juice browning and flavour changes.

- The impact of light on juice quality.

- Orange juice aroma and the effect of different package types on aroma retention.

- Different packaging systems.

Summary

One of the primary aims of a packaging system is to protect the product from microbial spoilage and chemical deterioration during distribution and storage. For orange juice, measures should be taken to protect vitamin C and flavour compounds, and to prevent microbial growth and colour changes.

Vitamin C is the compound in orange juice that reacts most readily with oxygen, and its loss correlates with the oxygen-barrier properties of the package. The degradation products of vitamin C contribute to browning.

Light, in combination with excessive oxygen (head-space and dissolved oxygen, and high oxygen permeation through the package), is known to accelerate flavour changes and aerobic degradation of vitamin C. Anaerobic degradation of vitamin C also takes place but independent of oxygen.

The culprits of quality loss

High storage temperatures combined with oxygen are the main factors involved in quality deterioration over time.

The results are loss of nutritional value concerning vitamin C, unpleasant colour changes, and off-flavour formation, which is caused predominantly by chemical changes in the juice matrix and, to a lesser degree, by changes in the volatile flavour fraction.

Almost all changes can occur under anaerobic storage conditions and are greatly accelerated by oxygen (headspace and dissolved oxygen, and oxygen permeating through the package).

In general, packaging for orange juice should contain an aroma barrier to prevent aromas permeating out through the package.

Laminated cartons rule

Laminated carton packages are the most common form of packaging in most countries for chilled and shelf-stable orange juice. They are either made from prefabricated blanks or fed from rolls. Worldwide, plastic bottles are the second most common type of container, followed by glass bottles.

9.1 The role of packaging

One of the main aims of a packaging system and packages is to protect orange juice from microbial spoilage and chemical deterioration during distribution and storage. The shelf life of food and beverages is the time period up to the point when the product becomes unacceptable from a safety, sensorial or nutritional perspective. The influence of packaging material and package type on the shelf life of orange juice has been the subject of many investigations.

Although the package is important in protecting its contents, it cannot improve the quality of orange juice made from poor raw materials or disguise quality degradation originating from non-optimal processing. Moreover, it is inevitable that product deterioration related to product-specific characteristics and storage conditions gradually takes place over time. Therefore, regardless of the package, degradation of vitamin C and browning of orange juice always take place in stored orange juice when a certain temperature and/ or storage time is exceeded.

In conclusion, the quality of orange juice at consumption depends on all the processing and packaging steps from raw material intake up to the product being consumed. Some important operating parameters which influence juice quality at different steps are presented in Figure 9.1.

9.1.1 Product quality parameters to be protected during storage

In addition to its most obvious function of containing the product, a consumer package must protect the specific quality parameters of orange juice. To better understand the term “quality parameters”, one could question why consumers buy orange juice. The main answers will most probably be its enjoyable taste and high nutritional value due to a high vitamin C content. Therefore, these quality parameters should be protected during a given shelf life.

This means taking measures to:

- Protect the relevant flavour compounds

- Protect the high vitamin C content

- Prevent colour changes

- Prevent microbial growth

9.1.2 Factors affecting quality parameters during storage

No packaging system is able to completely prevent changes in quality taking place in orange juice – or other beverages in general – during storage. From the day of processing to the day of consumption, the product will change to a certain extent dependent on storage conditions. And in most cases, with the possible exception of wines, the changes will be for the worse.

With regard to the quality parameters already identified for orange juice, the packaging and storage conditions given in Table 9.1 influence how long an acceptable quality can be retained during storage.

Table 9.1 Factors influencing shelf life

| Package properties | Storage conditions |

| Barrier against | • Oxygen |

| • Time | • Temperature |

| • Light | • Aseptic |

| • Flavour losses | • Non-aseptic |

| • Microorganisms |

Before looking more closely at package barrier properties, it is important to keep in mind that packaging can never be discussed without considering the intended storage conditions – particularly temperature and time – because these are the main determinants of barrier demands.

9.2 Barrier properties Against oxygen

Oxygen plays a major role in the loss of quality in orange juice during storage, mainly because of:

- Vitamin C degradation

- Colour changes (browning)

Several publications also indicate the negative impact of oxygen on flavour compounds and on off-flavour formation during the storage of orange juice at ambient temperature. This is, however, a contentious area that is a matter of some debate.

9.2.1 Vitamin C degradation

Vitamin C is the most oxygen-sensitive compound in orange juice. Its loss is thus closely related to oxygen content in packages. Generally, vitamin C is lost through two different chemical pathways – anaerobic and aerobic degradation. As its name implies, the anaerobic pathway is independent of oxygen and dependent mainly on storage temperature. Losses caused by anaerobic degradation cannot be prevented by packaging and are the same in all types of packages. The only possible counter-measure is to reduce storage temperature.

The aerobic pathway needs oxygen and is therefore strictly related to the presence of headspace oxygen and oxygen dissolved in the juice, as well as the oxygen-barrier properties of the package.

Both anaerobic and aerobic degradation take place simultaneously in orange juice. Which one dominates depends on storage temperature and oxygen availability.

For packages with good oxygen-barrier properties, for example glass bottles, anaerobic degradation plays the major role regarding total vitamin C loss. In cases where oxygen permeation into the package is considerable, headspace oxygen is present or oxygen is dissolved in the product, the contribution of anaerobic degradation to total vitamin C loss is small compared to aerobic degradation.

Examples of vitamin c loss for a 1-litre package during ambient storage based on stoichiometric calculation

Headspace A headspace volume of 5 ml air, containing 1 ml oxygen (about 21%), can theoretically oxidize approximately 15 mg vitamin C.

Dissolved oxygen 1 mg oxygen corresponds to a loss of approximately 11 mg vitamin C.

Anaerobic degradation

The anaerobic degradation corresponds to an approximate loss of:

1 mg/l vitamin C per month at 10°C

5 mg/l vitamin C per month at 20°C

20 mg/l vitamin C per month at 30°C

Oxygen permeating through the package

An oxygen permeability of 0.02 ml oxygen/ package/ day in a 1-litre package results in a loss of 9 mg/l vitamin C per month during ambient storage.

For a package with a permeability of 0.05 ml oxygen/ package/day the loss is 22 mg/l vitamin C per month.

Since both anaerobic and aerobic pathways for vitamin C degradation occur simultaneously in most packaged products, vitamin C degradation curves cannot usually be attributed to solely one pathway.

Figure 9.2 shows vitamin C degradation in orange juice stored at ambient temperature in two package types– laminated cartons with a barrier layer of aluminium (Al) foil in the first type and of a polymer, such as ethylene vinyl alcohol (EVOH), in the other. The Al-foil layer is a good oxygen barrier, whereas packages with a polymer barrier layer like EVOH allow higher oxygen permeability. Some packages were stored in an oxygen-free atmosphere, and in this case the vitamin C loss represents mainly the anaerobic degradation pathway.

It is quite obvious that when oxygen permeability of a package exceeds a certain point, the aerobic pathway predominates. The anaerobic reaction pathway is mainly temperature-driven. The impact of temperature can be seen from the example of a 1-litre package in the fact box.

Storage temperature is also important for aerobic degradation of vitamin C. Figure 9.3 shows the change in vitamin C content in orange juice during storage for 30 weeks at 4°C and 23°C respectively in the same package type (Tetra Brik Aseptic, TBA, 250 ml). The calculated vitamin C loss due to anaerobic degradation is indicated in the graph. The difference in vitamin C retention between storage at 4°C and 23°C is obvious. During 30 weeks storage, an increase in temperature from 4°C to 23°C results in increased losses of vitamin C of 28 mg/l due to anaerobic degradation, and 42 mg/l due to aerobic degradation.

The rate of oxidative degradation of vitamin C is slowed dramatically under chilled storage. Consequently, packages for chilled distribution do not need as high oxygen-barrier properties as packages stored at ambient temperature.

9.2.2 Colour changes

The colour of orange juice is primarily determined by its carotenoid content. However, carotenoids are relatively stable in orange juice since they are protected by vitamin C and are not regarded as being responsible for the colour changes that occur during long-term storage at ambient temperature

The colour changes, or rather the darkening, during storage are based on the appearance of brown-coloured compounds caused by the chemical reaction of orange juice components present in the juice matrix. The brown compounds are formed in the end phase of the so-called “Maillard Reaction” (also known as non-enzymatic browning), which is a well-known reaction between sugars and amino acids. This reaction type is generally not dependent on oxygen, but is clearly temperature-driven.

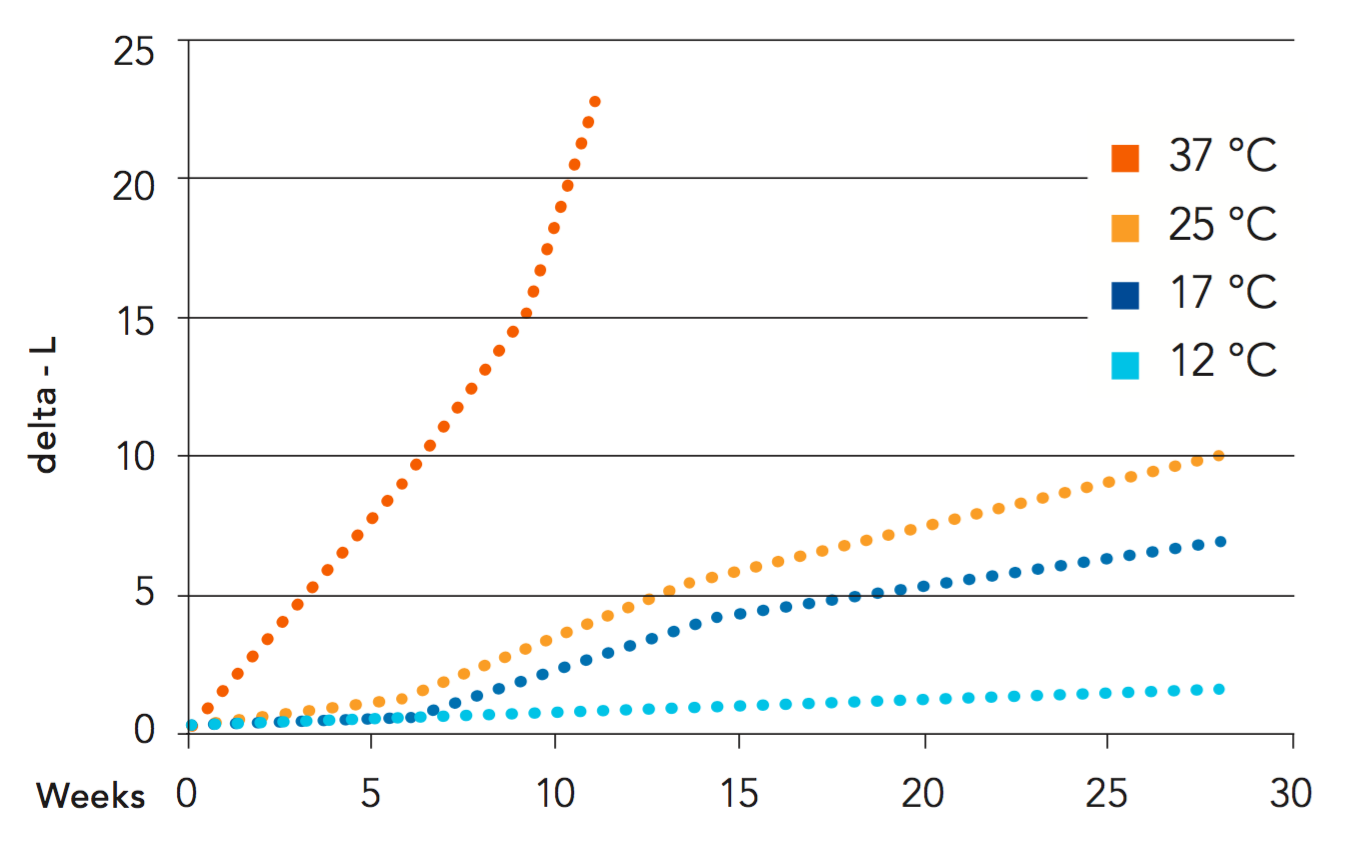

Figure 9.4 shows the effect of temperature on the browning of orange concentrate. It is evident that browning results mainly from long-term storage at temperatures higher than 12°C.

Vitamin C can participate in the development of browning through its degradation by-products generated both by aerobic and anaerobic pathways. Consequently, the oxygen barrier of a package influences browning because it determines the supply of oxygen to the aerobic pathway of vitamin C degradation.

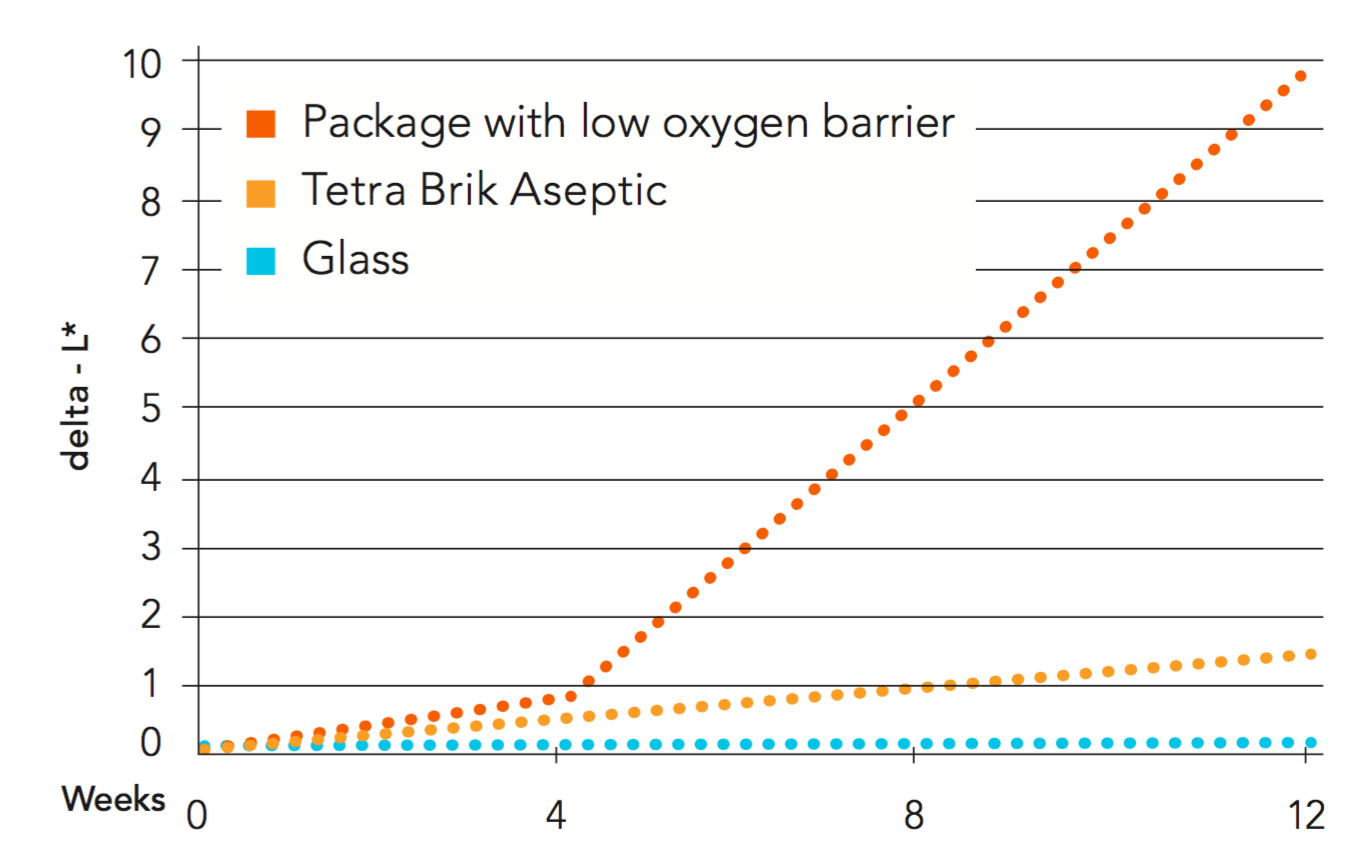

Figure 9.5 shows colour changes in orange juice in packages with different oxygen-barrier properties during storage at 23°C. There is a clear increase in browning with increased oxygen permeation through the package. This allows the conclusion that the better the package oxygen barrier, the lower the risk of browning.

Methods of measuring colour in orange juice are described in subsection 2.2.4.

9.2.3 The impact of oxygen on storage-dependent flavour changes

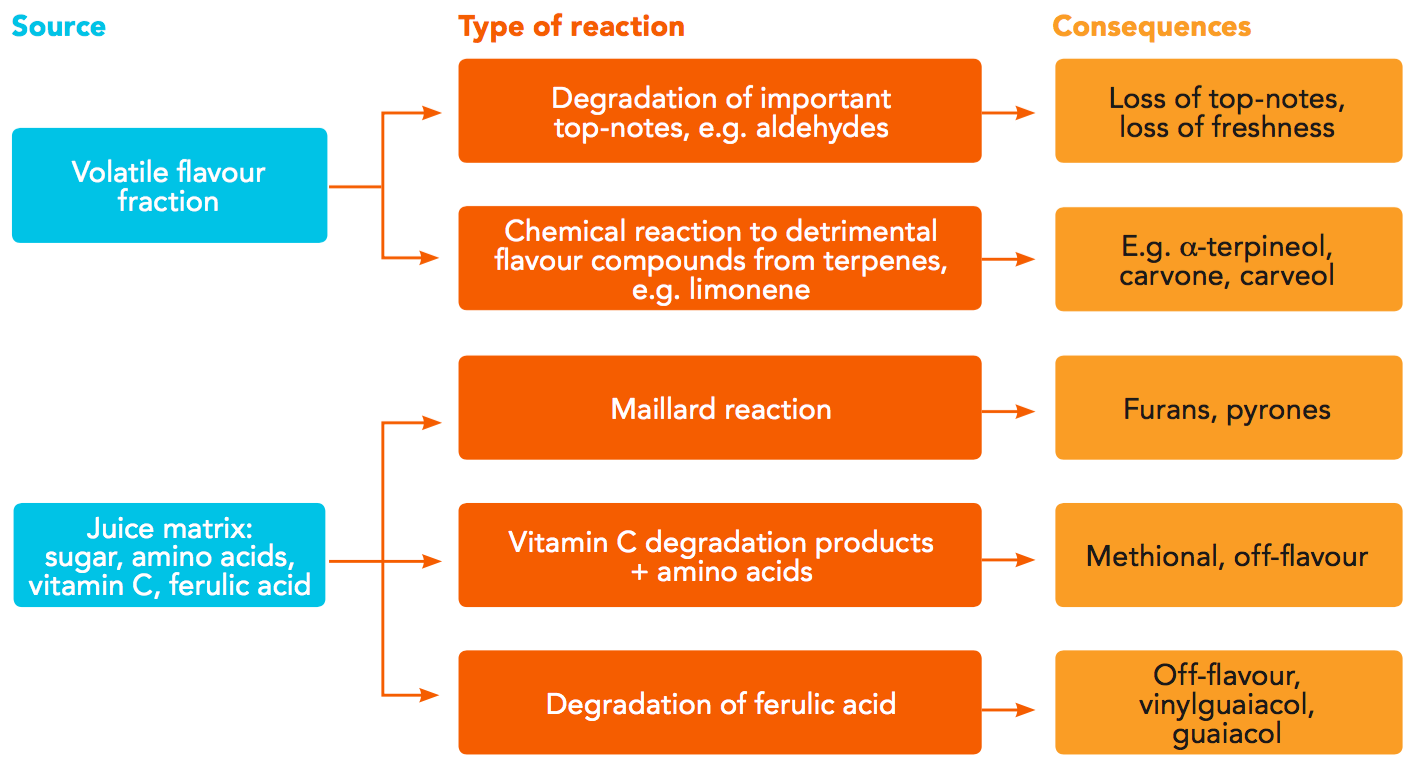

The orange juice flavour is composed of a broad mixture of different aroma fractions, which contain a variety of volatile compounds as described in more detail in subsection 9.4. These aroma compounds may undergo several changes during storage that gradually lead to a loss of freshness and the formation of an unpleasant aroma (off-flavour). Most of these changes are acid-catalysed reactions, which are supported by the acidity of the juice and accelerated by high storage temperatures.

Degradation pathways of important aroma fractions like aldehydes include oxidative reactions. Thus, it cannot be excluded that oxygen content and hence the oxygen-barrier properties of the packaging solution have an impact on the aroma of the packed orange juice. However, as vitamin C is a quantitatively important antioxidant in orange juice and immediately reacts with available oxygen, the impact of oxygen on the aroma is less pronounced as long as vitamin C is present.

Three compounds have been identified as important off-flavour contributors in orange juice, independent of the packaging used. These compounds, which gradually develop in juice, are:

- 4-vinyl guaiacol (PVG)

- 2,5-dimethyl-4-hydroxy-3(2H)-furanone (DMHF)

- alpha-terpineol

When these compounds are added to freshly prepared orange juice, PVG imparts an old fruit or rotten fruit aroma; DMHF imparts a pineapple-like aroma typically found in old orange juice and alpha-terpineol is described as stale, musty or piny.

The formation of PVG results from storage-induced changes in the juice matrix, DMHF results from the so-called Maillard reactions between carbohydrates and proteins, and á-terpineol is a degradation product of the aroma compound limonene. All three reactions are supported by the acidity of the juice and storage temperature. Since vitamin C’s oxidative degradation products can participate in the Maillard reactions, the package oxygen-barrier properties (and thus a more pronounced vitamin C decay) can to a certain extent also impact the sensory properties of orange juice, primarily colour (browning) and, to a lesser degree, flavour.

Figure 9.6 gives an overview of the flavour changes that occur in orange juice during storage.

9.3 Barrier properties against light

Light is known to accelerate the aerobic (but not an-aerobic) degradation of vitamin C. One can therefore conclude that:

- Light has an effect only when oxygen is present. Consequently, packages with high oxygen-barrier properties, such as glass and high-barrier PET bottles, do not need a light barrier.

- During storage at ambient temperature in packages with a good oxygen barrier, low oxygen permeation rates limit the rate of vitamin C degradation. Moreover, all oxygen entering through the package is almost immediately consumed. Thus, light cannot accelerate the reaction and therefore has no significant impact.

- During chilled storage, for which packages with higher oxygen permeability are mainly used and the reaction between vitamin C and oxygen is significantly slowed down, oxygen will accumulate in the product. Light can then accelerate vitamin C degradation.

As a result, light protection should be primarily considered for use in packages for chilled distribution that have low oxygen-barrier properties.

Hydrocarbons A group of compounds that contain only hydrogen and carbon in their molecular structure. Example: d-limonene

Alcohols, aldehydes and esters contain only hydrogen, oxygen and carbon in their molecular structure.

Alcohols Typical functional group: R-OH Example: linalool

Aldehydes Typical functional group: R-CHO Example: hexanal

Esters Typical functional group: R-COOR Example: ethyl butyrate

R = a particular molecular side chain

The concentration of an aroma compound cannot be correlated directly with its importance for flavour

9.4 Barrier properties against aromas

In most cases, orange juice packaging is required to provide a barrier that prevents aroma compounds from permeating out through the package. Another requirement of packaging is to provide a barrier against odours from the surrounding atmosphere entering the packaged orange juice. This subsection discusses the composition of the aroma fraction in orange juice and the properties of different polymers and different packages commonly used.

9.4.1 Composition of orange juice aroma

Orange juice aroma, as a term generally used in this section on packaging, includes all the volatile compounds of orange juice flavour. Hence it is not identical to “essence aroma” (or water-phase aroma), which is the water-soluble volatile fraction recovered in the essence recovery unit during evaporation. See also section 2.2.

Orange juice aroma is a complex mixture of many volatile compounds. In chemical terms, it is mainly a mixture of hydrocarbons, aldehydes, alcohols and esters (see fact box). The predominant fraction consists of hydrocarbons, of which one single compound, d-limonene, accounts for more than 90% of the total aroma fraction. The aroma oil content of orange juice is usually evaluated by a standard test method (Scott titration), which more or less reflects d-limonene content only. Therefore, limonene loss during packaging and storage is often incorrectly equated to flavour loss.

It is not possible to correlate directly the relative concentration of an aroma compound with its importance for flavour. For example, a compound that is 90% w/w of the aroma fraction may contribute very little to the flavour, whereas a compound that has only a 0.001% w/w share of the aroma fraction may have a very high impact on the flavour sensation. The reason is that the human nose and taste buds can respond very differently to compounds of different chemical structure.

Besides specific knowledge about the composition of aromas, it is also essential to identify those individual aroma compounds that contribute most to taste and smell of the product.

Table 9.2 The contribution of volatiles to orange juice aroma

| Contribution to typical aromas | Contribution to off-aromas |

| Important | Desirable | Precursors | Detrimental |

| ethyl butyrate | linalool | linalool | α-terpineol |

| neral | limonene | limonene | carvone |

| geranial | α-pinene | valencene | t-carveol |

| valencene | nootkatone | ||

| acetaldehyde | hexanal | ||

| octanal | t-2-hexenal | ||

| nonanal | hexanol | ||

| α-sinensal | 4-vinyl guaiacol | ||

| ß-sinensal | 2,5-dimethyl- | ||

| 4-hydroxy- | |||

| 3-(2H) furanone |

Source: Dürr et al.

Dürr et al. (1981) categorized juice aroma compounds in four groups, listed in Table 9.2. The categories remain valid today:

- Important

- Desirable

- Off-odour precursors

- Detrimental

Off-odour precursors are compounds that can undergo chemical changes during storage leading to undesirable off-odours, even if the original compounds themselves may contribute positively to orange aroma. Limonene, linalool and valencene are examples of off-odour precursors.

P = D× S

Permeation rate = Diffusion × Solubility

9.4.2 Properties of different polymers

Aromas can be absorbed into or permeate through the packaging material depending on the type of aroma compound (chemical class, polarity) and the nature of the packaging material. This effect, often called “flavour scalping”, has been extensively studied, especially for laminated carton packages.

The absorption and/or permeation of aroma compounds through polymers is based on the general equation that permeation (P) is a product of diffusion (D) and solubility (S), P = D×S. Consequently, only those aroma compounds with high diffusion and solubility coefficients in respective polymers are likely to be lost through permeation or absorption during storage. The solubility of a compound in a polymer can be estimated simply by making use of the fact that “like dissolves like”.

In non-polar polymers, such as polyolefins, non-polar aroma compounds like limonene have high solubility. Low-density polyethylene (LDPE), high-density polyethylene (HDPE) and polypropylene (PP) are examples of polyolefins. While there is a minor difference in solubility for non-polar aroma compounds in the stated polyolefins, their diffusion and consequent permeation rates differ by orders of magnitude in the different polyolefins - in decreasing order LDPE>HDPE>PP. Aroma losses into the polymer layer are therefore significantly slower in PP and HDPE than in LDPE.

Unlike non-polar components, polar components such as ethyl butyrate have low solubility in polyolefins. As a result, their permeation rates are very low and losses due to permeation are negligible in barrier packages with LDPE as product-contact layer.

Polar polymers like polyester (PET), EVOH and polyamide (PA) basically show very low diffusion coefficients with polar and non-polar aroma compounds. This results in good barrier properties against both types. However, polar polymers are sometimes more difficult to heat-seal than polyolefins.

In summary, aroma losses due to absorption into or permeation through polymer packaging primarily involve non-polar aroma compounds (for example hydrocarbons like limonene) in contact with non-polar polymers (LDPE, HDPE, PP) commonly used as sealing layers. Polar polymers (PET, PA, EVOH) exhibit minimal absorption of aroma compounds and thus provide an effective aroma barrier.

9.4.3 Properties of different packages

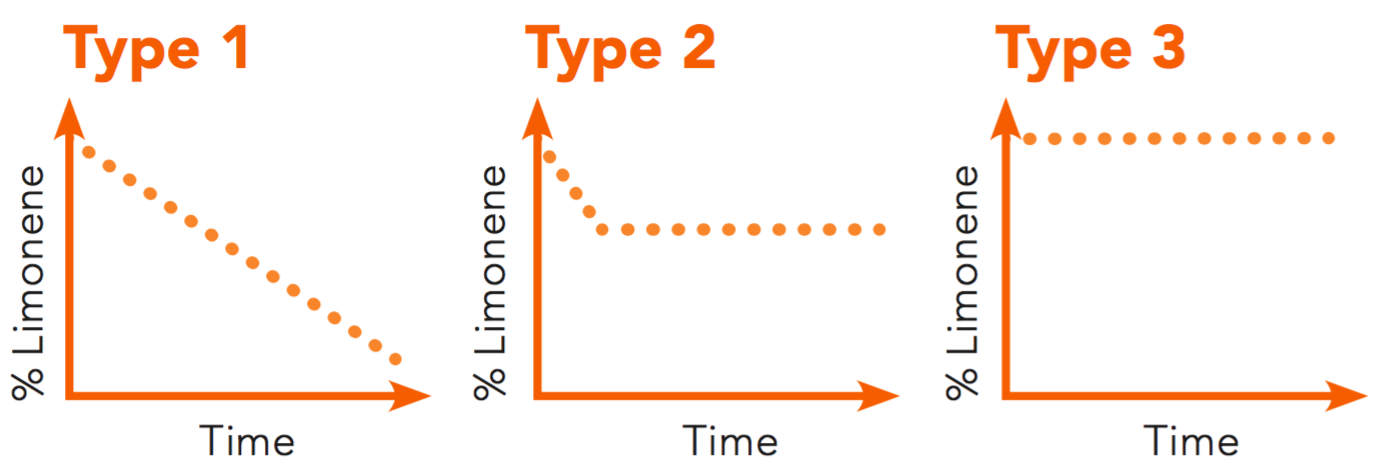

The extent of loss of aroma compounds due to absorption or permeation can vary significantly between different package types. Generally speaking, three package types can be distinguished as shown in Figure 9.7:

- Type 1 package has no efficient aroma barrier (for example carton packages without a barrier layer and monolayer HDPE bottles).

- Type 2 package has an aroma barrier not in contact with product, and a sealing layer like LDPE in contact with product. Most laminated cartons are type 2 packages. Also, HDPE bottles incorporating a barrier layer belong to this group.

- Type 3 package has an aroma barrier in direct contact with product (for example glass and PET bottles).

Because absorption and permeation mainly involve non-polar aroma compounds, limonene is a key compound in monitoring flavour scalping. For the three package types, the loss of limonene can be demonstrated using the graphs shown in Figure 9.8.

Type 1

Limonene content decreases continuously by permeation through the package due to the absence of an aroma barrier. The loss over time depends mainly on the choice of polyolefin polymers, and the slope of the curves is determined by the diffusion of limonene into the individual polymers. For a given shelf life, such as nine weeks, the limonene loss in PP would therefore be lower than in LDPE.

Type 1 packages cannot be used for long-term storage of orange juice at ambient temperature because of the extensive loss of aroma compounds. Moreover, the absence of an aroma barrier also implies the lack of an oxygen barrier. (Oxygen barriers are generally also good aroma barriers.) It is possible to use Type 1 packages for orange juice stored chilled for a few weeks, as is done in the US market with monolayer HDPE bottles. The low diffusion coefficient of HDPE limits aroma loss within the short shelf-life period. When significant loss of quality needs to be prevented, laminated carton packages based on LDPE as sealing polymer need an aroma and oxygen barrier, even under chilled storage conditions.

Type 2

In this package, which has an aroma barrier and a polyolefin sealing layer in contact with product, limonene content will decrease within the first few weeks of storage due to its absorption into the sealing layer. As soon as this layer is saturated with aroma compounds, an equilibrium level will be reached and no further absorption/permeation will take place because the effective barrier (such as Al-foil, PET, PA, EVOH) behind the sealing layer prevents further permeation through the material structure.

The extent of limonene retention at equilibrium is determined in this package type by the thickness of the internal sealing layer and by the ratio of internal surface area to product volume of the packages. The larger the package size and the lower the internal coating thickness, the higher the limonene retention. Saturation will be reached after 2-4 weeks at ambient temperature. HDPE bottles that comprise a middle layer of barrier material (such as EVOH) show similar patterns of aroma absorption.

Type 2 packages are used extensively for orange juice distributed at ambient temperature or under chilled conditions.

Type 3

In this package, the aroma barrier is in direct contact with product and practically no limonene absorption or permeation takes place. The slight loss of limonene that occurs during storage at ambient temperature is related only to chemical degradation, which is independent of the packaging. Type 3 packages are mainly glass and PET bottles. In flexible packages, aroma-barrier polymers simultaneously used as sealing layers are sometimes more difficult to seal than polyolefins.

9.4.4 Consequences of flavour scalping

Laminated cartons used for orange juice packaging are often Type 2 packages, which allow a certain degree of flavour scalping.

However, absorption into this package type does not affect the whole aroma profile but rather the non-polar aroma compounds like limonene. Nevertheless, the barrier (Al-foil) in the laminate structure limits the loss of non-polar aroma compounds.

The question thus arises of whether flavour scalping has a significant impact on juice quality and taste. This subject is a matter of controversy in the literature. Dürr et al. (see Table 9.2) ranked the hydrocarbon fraction of orange juice aroma mainly under the desirable portion. However, they also indicated that limonene, for instance, is a precursor for development of off-odour during storage. They showed that losses of up to 40% of limonene actually had no effect on the sensory quality of orange juice during 90 days’ storage at 20°C, and suggested that limonene made a low contribution to the typical aroma of orange juice.

Joint investigations between Tetra Pak and the Citrus Research Centre in Florida (Pieper et al. 1992) showed that flavour scalping of up to 50% of the original concentration of limonene in orange juice has no effect on the sensory ranking in a preference hedonic scale test of quality of orange juice stored for up to 23 weeks at 4°C.

Although absorption of limonene into the inner layer of barrier packages was found not to affect the taste of the juice, additional aroma oil is sometimes added in juice preparation to compensate for any loss caused by limonene absorption, for example when the same product is distributed in several different package types.

The term flavour scalping is widely used in publications to mean the almost exclusive absorption of limonene into the internal polyethylene coatings of laminated carton packages.

As limonene contributes little to orange juice flavour, the loss of limonene does not correlate with the loss of flavour in a product.

9.5 Aseptic versus non-aseptic packaging

For storage at ambient temperature, it is essential that:

- Orange juice is free from spoilage microorganisms when packed

- Packages do not recontaminate the product

- Packages provide an effective barrier against external microorganisms

Since these conditions are an absolute prerequisite for storage at ambient temperature, product shelf life is not determined by microbiological factors but by quality changes that are due to inevitable temperature-driven reactions and oxidative reactions. The latter are directly related to the package barrier properties.

For juice under chilled distribution, the situation can be more complicated. Microbial spoilage may become the limiting factor of shelf life depending on the selected heat treatment of the product, hygienic status of the packaging system and storage temperature of filled packages (2-10°C).

It is outside the scope of this section to discuss the different options with respect to expected shelf life under chilled conditions, but it is important to understand that the requirements for other barrier properties of a package depend on whether or not product shelf life is limited by microbiological spoilage. For example, if a juice is spoiled by microbial action after three weeks at 4°C, the aroma and oxygen barrier properties are of minor importance compared with a package where the juice is spoiled by microorganisms after six weeks or more. In this case, enhanced aroma and oxygen barrier package properties are required to meet the extended shelf life.

For aseptically packed juice, the oxygen and aroma barrier properties of the package determine product shelf life because there is no microbial action.

Figure 9.9 presents the factors that affect product shelf life and their relative importance during chilled and ambient distribution.

9.6 Different packages and packaging systems

Orange juice for home consumption is sold mainly in shelf-stable or chilled form. The shelf-stable form, stored at ambient temperature, dominates all global retail markets except in the US, where chilled juice leads. Frozen concentrate for home dilution was popular in the US but has declined to a minor product. It is rare elsewhere because of poor quality domestic water or the inconvenience of dilution.

Ready-to-drink juice from concentrate and NFC sold as shelf-stable products are pasteurized and either packaged aseptically or hot filled. The types of orange juice sold in chilled form – freshly squeezed juice, NFC and ready-to-drink juice from concentrate – are not usually packaged aseptically or hot filled.

Laminated carton packages are the predominant form of orange juice packaging in most countries. Worldwide plastic bottles are the second most common type of container, while glass bottles today play a minor role in orange juice packaging. Nevertheless, in some markets like France and Germany certain consumer groups still favour glass bottles. Today, less and less juice for consumption is sold in cans, although Japan is one exception. PET, usually with an added oxygen barrier, is the most common material used for plastic bottles containing ambient orange juice. In bottles for chilled juice a shift is under way from HDPE to PET.

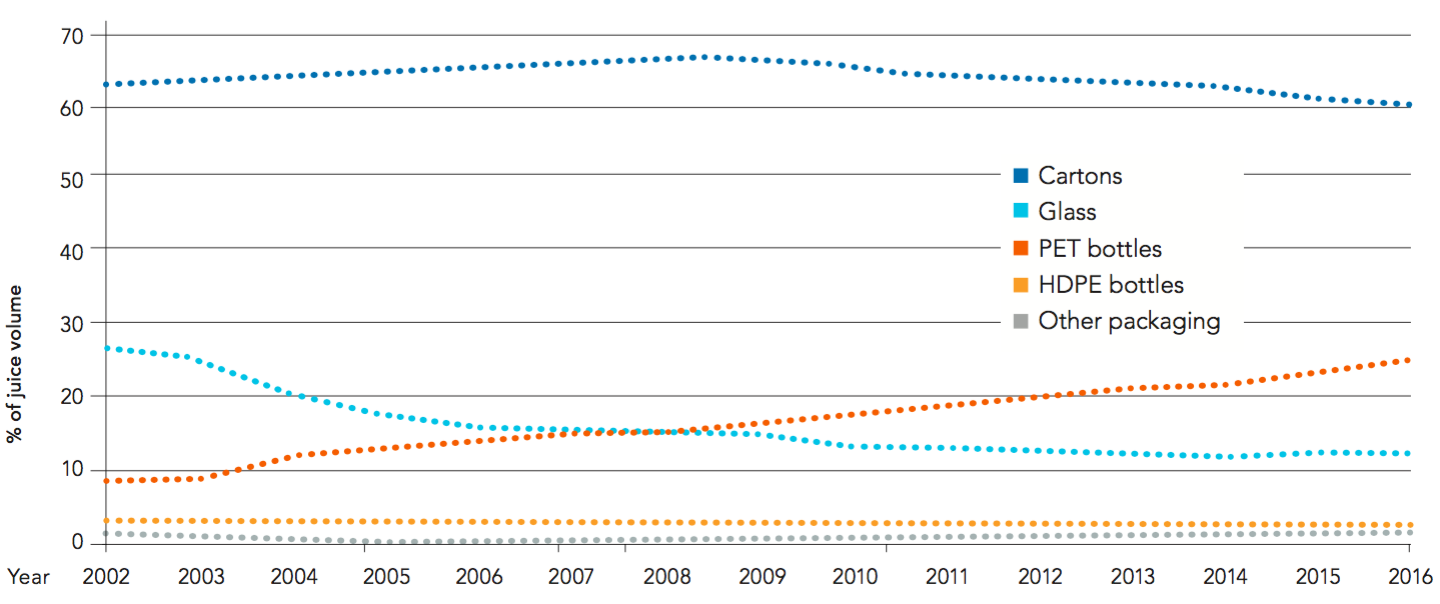

The packaging preferences for fruit juices (all flavours) in Europe can be seen in Figure 9.10.

9.6.1 Carton-based packages

The laminated carton material normally consists of layers of paperboard coated internally and externally with polyethylene, and a barrier layer.

The most commonly used barrier layer today is Al-foil. Other barriers include ethylene vinyl alcohol (EVOH) and polyamide (PA). A schematic structure of laminated packaging material for orange juice cartons is shown in Figure 9.11. Depending on the packaging system used, the packaging material is delivered to the juice packer as prefabricated carton blanks or printed and creased in rolls.

Oxygen-barrier properties of a laminated carton package depend not only on the barrier properties of the packaging material itself, but also on the barrier properties of strips and closures and the tightness of seals.

Carton-based packages from prefabricated blanks

With prefabricated systems, the blanks are die-cut and creased, and the longitudinal seal is completed at the packaging material factory. The printed flat blanks are delivered to the juice packing facility, where they are finally shaped and sealed in the filler.

Blanks to be used for chilled orange juice are handled under non-sterile conditions but steps are taken to avoid recontamination of microorganisms. The filling temperature should be low (4-5°C or less) to minimize microbial growth. At these low temperatures the risk of foaming is higher compared with filling at higher temperature.

All packages made from prefabricated blanks are filled by leaving a certain amount of headspace. An inert gas like nitrogen can be used to flush the headspace to remove some oxygen and decrease oxidative changes in the juice during storage. The advantages of a headspace are that pulp-containing juice can be shaken, and that package sealing occurs above the product level, thus preventing floating pulp from getting trapped in the top seal.

The filling of juices containing floating pulp should be done continuously because separation of the juice and cells in upstream buffer tanks happens quite fast. To avoid separation, agitation of upstream tanks is sometimes carried out. Care should be taken to prevent agitation from introducing air and gas bubbles into the juice.

Some packages made from prefabricated blanks are shown in Figure 9.12.

Carton-based packages from rolls

Packaging materials are supplied in rolls that have been printed and creased. The packaging material roll is fed into a machine, where it is formed into a tube and the longitudinal seal made by a heat-sealing system. In this process, a strip is heat-sealed along the inner surface of the longitudinal seal (LS) to protect the different layers of packaging material from contact with product and vice versa. The oxygen-barrier properties of the longitudinal seal are important for oxygen-sensitive products such as orange juice.

Juice is poured into the tube and a transversal seal (TS) is made below the level of the orange juice. This results in headspace-free packages. Alternatively, packages may be produced with a headspace either through nitrogen injection or low-level filling. Packaging without headspace or with an oxygen-free headspace is advantageous for orange juice and other oxygen-sensitive products because it eliminates a significant source of oxygen and associated quality changes.

Carton-based packages with a polyethylene top are made from roll-fed packaging material as well. In the filling machine the material is cut into sheets, which are folded and longitudinally sealed. The plastic tops are injection-moulded and sealed with the sleeve to form a package. After filling from the bottom, the bottoms are sealed by heating elements.

Figure 9.13 shows various carton-based packages - with and without headspace - made from rolls.

In an aseptic filling system, the material web is sterilized with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) or by electron beam. Hydrogen peroxide is used either in a wetting system or a deep bath system, after which the H2O2 is completely evaporated.

In electron beam sterilization, the packaging material passes in front of an e-beam lamp that emits a jet of high-energy electrons that kill microorganisms on the material surface. Less energy is used for e-beam sterilization as heating and drying of H2O2 is not required.

The subsequent filling and sealing processes are all performed inside a sterile chamber under positive pressure.

Seal quality is of utmost importance in aseptic systems to prevent the entry of microorganisms. When filling orange juice with a high content of floating pulp, special consideration should be given to the transversal sealing.

9.6.2 Glass bottles

Glass bottles still play an important role in several markets worldwide. For shelf-stable orange juice in glass bottles, the most common filling method is hot filling. Aseptic filling of glass bottles at ambient temperature is of minor importance compared to hot filling. Of the package types used today for orange juice, glass bottles are normally considered to have the best oxygen barrier properties.

In hot filling, the deaerated and heated juice is directly poured into cleaned bottles that are capped. The filling temperature is usually between 90°C and 98°C. Preheating of glass bottles is necessary to reduce the

risk of glass splintering at filling. The required holding time for capped hot bottles, prior to cooling in a tunnel, depends on the level of microbial contamination of the empty bottles.

The hot product sterilizes the inside surface of the bottle, whereas bottle closures should be sterilized before they are applied to the bottle. Prior to closure, the bottle neck is flushed with steam. Steam injection keeps foaming to a minimum and reduces the oxygen content of the neck space as well as the recontamination risk. Hot filled bottles are frequently overfilled in order to ensure sterilization of the neck by the hot product. Other possibilities for neck sterilization are to tilt the bottle or turn it upside down.

9.6.3 Plastic bottles

Blow-moulded plastic bottles are today the dominant bottle type for orange juice, far exceeding the use of glass bottles. The most common plastic bottles are polyethylene terephtalate (PET) followed by high-density polyethylene (HDPE).

HDPE bottles

As HDPE has a poor oxygen barrier, plain HDPE bottles allow relatively high oxygen ingress and are used for chilled juice of short shelf life only (about three weeks). The oxygen barrier can be improved by adding intermediate layers of polymers with superior barrier properties. The most common barrier layers in HDPE bottles for orange juice are ethylene vinyl alcohol (EVOH) and polyamide (PA). These also provide an aroma barrier and can allow ambient storage for six months or longer, depending on the choice and thickness of the barrier layer.

HDPE bottles are fairly opaque, often pigmented, and produced by the extrusion blow-moulding (EBM) process. Contrary to PET, HDPE bottles exhibit high thermal resistance and can be hot filled as well as sterilized in autoclaves. With the increased use of aseptic filling, however, ambient orange juice has shifted from HDPE to transparent PET bottles.

In extrusion blow moulding (EBM), the HDPE resin is first melted in a hot screw and pushed through a steel disk (a die) to form a hollow pipe of polymer known as a parison. When the parison is sufficiently long, the two halves of the bottle mould close around it. Then pressurized air blows into the parison so it takes the shape of the mould, thus the bottle is formed. The bottle is blown with a sealed dome that must be cut off before filling.

A barrier layer may be incorporated by co-extruding barrier material with HDPE in the parison. Barrier bottles typically comprise six or seven layers, including intermediate tie-layers and regrind material.

Bottles with an integrated handle can be made using the EBM process. EBM can also be used to produce PET bottles provided special grades of modified PET resin are employed.

PET bottles

PET bottles were introduced in the late 1970s for carbonated beverages. Their use has grown steadily in most beverage applications. Today, they are the most common container for still and carbonated drinks. Orange juice packaged in PET bottles is found in both the chilled and ambient segments; ambient juice is either filled aseptically or hot filled.

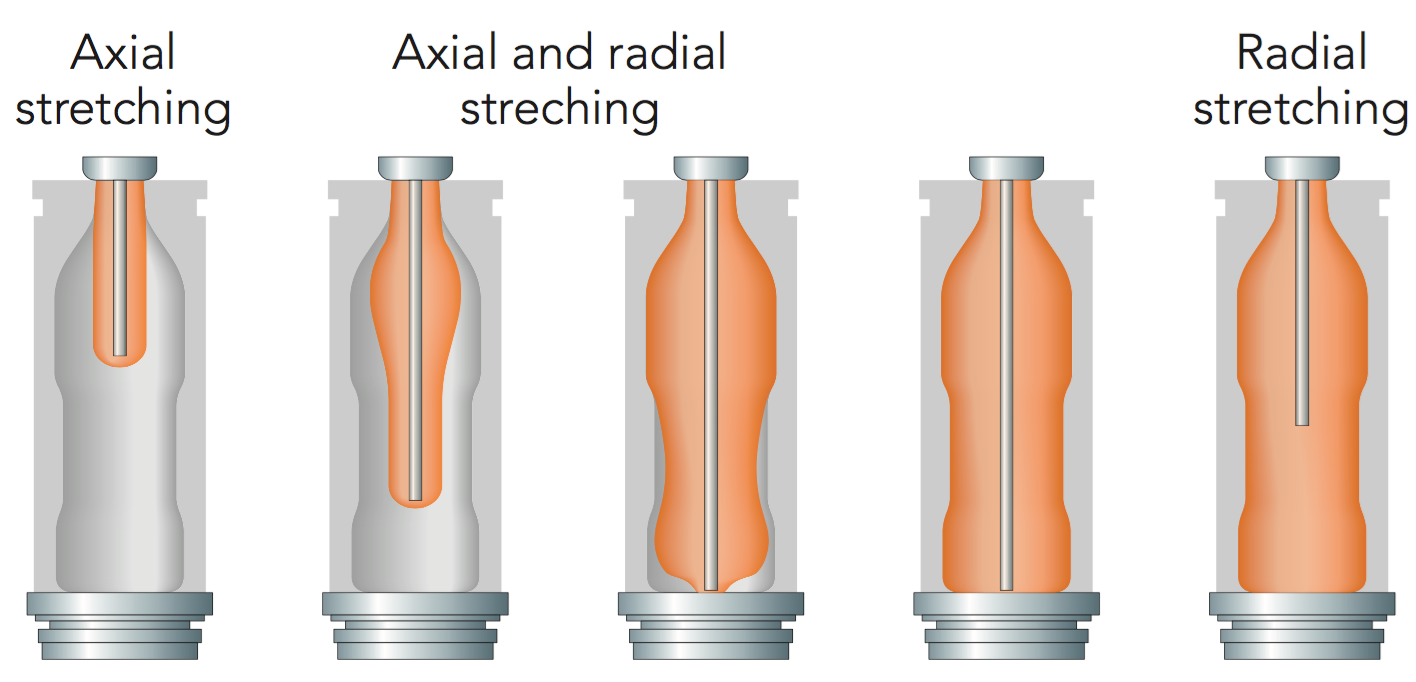

PET bottles are made by stretch blow moulding (SBM), starting with a preform. A preform is an injection-moulded PET tube closed at one end and with the finished neck at the open end. During blowing with high-pressure air, the heated preform is stretched both axially (using a stretch rod) and radially into the bottle mould (see Figure 9.16). The bi-oriented material gives the bottle high tensile strength and an increased gas barrier, which allows for lightweight bottles.

Stretch blow moulding equipment is available for all capacities: from small units for 6,000 bottles per hour to mega-systems producing 100,000 bottles per hour. There are also systems with integrated preform injection and bottle blowing (ISBM), starting with PET resin in-feed and a blown bottle out the other end.

In their natural state, PET bottles are transparent and colourless. However, it is possible to produce coloured bottles by adding appropriate pigments to the raw PET material.

Adding barrier to PET

The robustness of PET bottles compared to glass is obvious, but they do not provide as good an oxygen barrier as glass. Standard PET bottles give a shelf life for orange juice of about three to four months; large volume bottles give a longer period. The inclusion of active (oxygen scavengers) and passive barriers in PET bottles may extend shelf life up to 12 months and more.

There are three main technologies for increasing PET bottle oxygen barrier properties. All three are applied to orange juice packaging:

- Monolayer barrier preform, where the PET polymer is mixed with an additive compound (such as oxygen scavenger) during preform production

- Multilayer preform, with three co-injected layers: PET/barrier material/PET. The barrier material is an oxygen scavenger mixed with PET. Polyamide (PA) is mainly used for CO2 gas retention, and can also be added to the oxygen scavenger.

- Bottle coating, using plasma technology to coat the inside of the bottle with a barrier layer. This technology requires an additional machine between bottle blowing and filling.

In many markets, PET bottles are collected and recycled into resin for use in new PET bottles. Compounds added during PET bottle production, including barrier additives, may reduce the quality of recycled PET material.

Increased heat resistance in PET

Amorphous (non-crystalline) PET becomes “rubbery” at temperatures above 70-80°C. Hence, regular PET bottles are not suitable for hot filling of orange juice, which is normally carried out at 84-88°C. To withstand these high fill temperatures, the bottles’ heat resistance is increased by applying special conditions during stretch blow moulding. Such “heatset” bottles are blown in a hot mould to achieve higher crystallinity and minimized stress in the PET material.

When the hot product cools down after filling, a vacuum forms inside the capped bottle because the volume of the liquid decreases and headspace gases are absorbed into the juice. PET bottles for hot filling are therefore designed with “vacuum panels” (flat surfaces on the side of the bottle) or other features that absorb the volume variations between hot and cold conditions.

PET bottles for aseptic filling do not require heat setting as filling takes place at room temperature. They are usually of lower weight than hot fill bottles and allow more freedom in their design as vacuum panels or similar features are not needed. As a result, bottle costs are lower but aseptic filling is more complex and entails a higher capital investment.

9.6.4 Hot filling

Ambient orange juice in plastic bottles may be filled aseptically or hot filled. In the US, hot filling is the dominant practice for shelf-stable still beverages, as for orange juice. At European juice packers, however, aseptic filling prevails for orange juice in cartons as well as plastic bottles. In Asia, both systems are employed.

Hot filling for the production of shelf-stable orange juice involves pouring the heat-treated juice, without significant cooling, directly into the package. The high temperature of the juice is used to kill microorganisms on the package surfaces. The time period and temperature needed will depend on:

- Microbial contamination of packages and closures

- Number of microorganisms in the surrounding air, production area and filling machine

- Quality requirements for the product

- pH value of the product

- Shape of the package

- Material used for packaging

Glass bottles have to be heated before filling and cooled after filling by means of a cascade system; otherwise the glass will break. PET bottles have the advantage of tolerating immediate exposure to high filling temperatures and cooling rapidly after the hold time needed to kill spoilage microorganisms.

9.6.5 Aseptic filling

Aseptic filling technologies for orange juice in plastic bottles demand a considerably more complex installation than basic hot filling. Prior to filling with product, the PET (or HDPE) bottles are sterilized using a sterilant such as peroxyacetic acid (PAA) or hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Bottles treated with PAA solution are then rinsed with sterile water, while bottles sterilized with H2O2 are dried with sterile air or nitrogen.

Several recent aseptic installations feature the sterilization of PET preforms instead of the blown bottles. The advantages of this approach include lower sterilant usage (H2O2 vapour) and possibilities to further decrease bottle weight. However, sterile conditions must be guaranteed during bottle blowing and transfer to the filling carousel. It results in a compact installation as SBM and filler are directly connected in a single block.

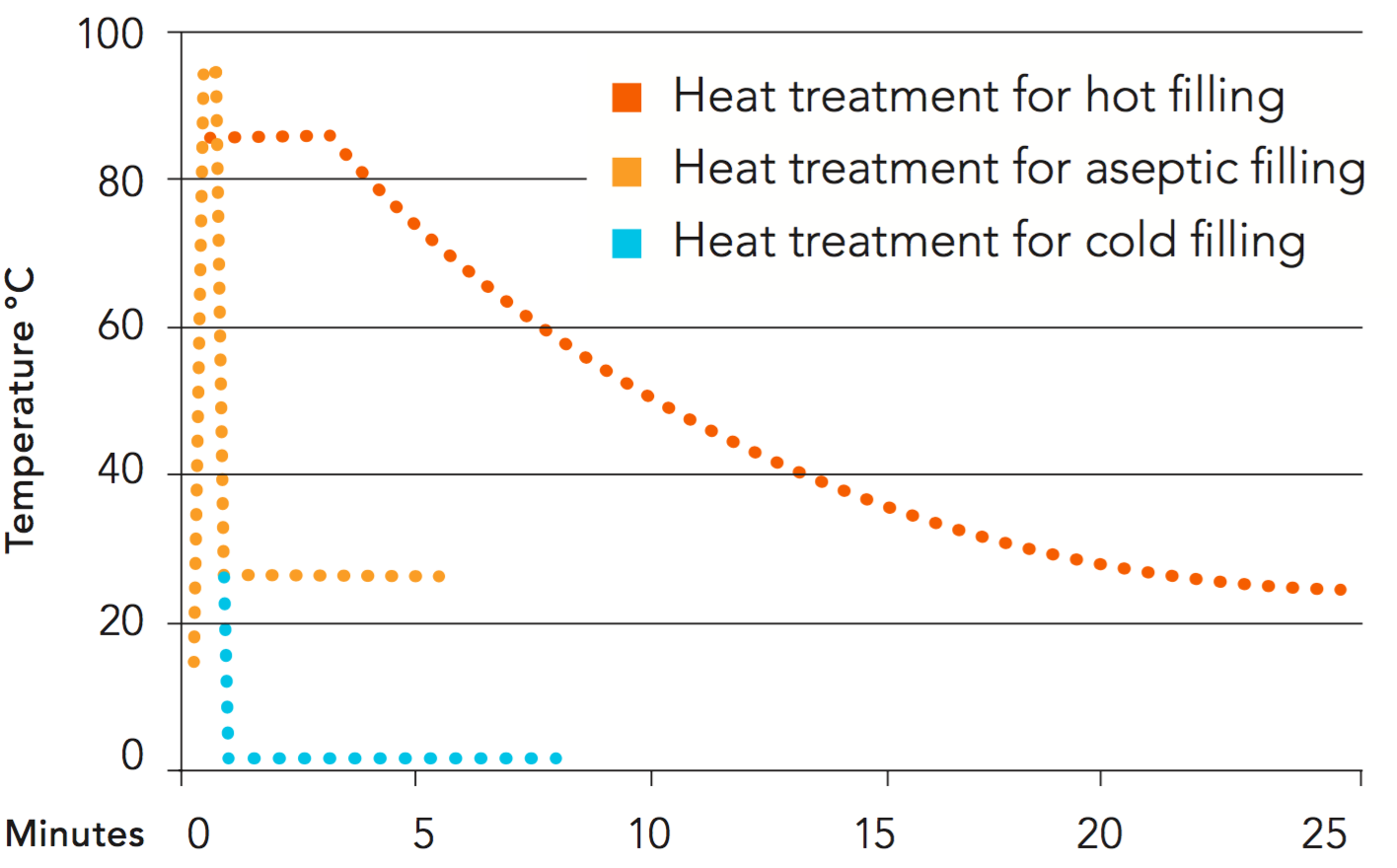

Figure 9.17 shows the heat treatment to which orange juice is subjected during aseptic filling and hot filling. For aseptic filling, the pasteurized juice is quickly cooled to filling temperature, whereas the time required to cool hot filled juice to ambient storage temperature is considerably longer. The cooling time depends on the bottle size and type of tunnel cooler.

9.6.6 Selecting the most appropriate package for a particular juice

To facilitate selection of the most appropriate packaging system for a particular juice, certain questions need to be answered. Some are listed below:

- Which quality parameters should the packages protect and to what extent? One answer is the minimum vitamin C content at the end of product shelf life.

- How long is the expected product shelf life and at what storage temperature?

- How many of the parameters limiting product shelf life are left after processing?

- Is dissolved oxygen present in the orange juice and to what extent?

- Which oxygen barrier is needed to protect the selected quality parameters during the intended shelf life?

- Is a light barrier needed?

Whatever packaging system is selected, the ultimate aim must be to maintain the quality of a particular orange juice product during its defined shelf life conditions.